"Learn by Doing": A Convo with Annie Nocenti about Superheroes and Mentors, Present and Invisible, Part I

Incl. Alexander Calder, Marie Severin and the Marvel Comics bullpen, Henry Miller, Francis Ford Coppola, Harold Channer, Robert Frank, June Leaf, and Gregory Corso

Maybe I didn’t so much show it, but I freaked out a little bit the first time I spoke to Ann Nocenti with an understanding of who she is. We had spoken other times before — Annie, one more artist and New Yorker whom I was lucky enough to cross paths with at bohemian wonderland Brazenhead Books — but all of that was before I understood she had edited or written several of the comic books I read avidly when I was a kid. At a party when she stated she had written Daredevil and invented the character’s nemesis Typhoid Mary, I asked her to repeat herself: dumb shock sometimes registers that way, I guess. It isn’t that I think of myself as a dumb person exactly, but my reaction was more expressive of the shock of the midwestern kid I was when those comic books, both figuratively and literally, lined the walls of my mind. Then, when I grasped that she had edited the X-Men too, during my favorite era of X-Men comics no less, and played a role in creating the character Longshot, well… It was just about over for me. I was coming to understand that all that my imagination had built up so mightily when I was a kid in St. Louis, Missouri had been created by someone, who could wind up standing right in front of me, in a room, smiling, chatting, and actually really appear to be enjoying herself.

If you’ve read Michael Chabon’s modern classic The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, then you understand pretty well the sorts of dynamics that can drive a boy to nest in comic books. I had anxiety of various kinds. I was, for a number of those years, decidedly undersized. Perhaps most importantly, my dad, a lapsed Catholic, who like his older brother had been drafted to serve during the final years of the Vietnam War, read comic books—kept a stack of Detective Comics in his half-open sock drawer in some my earliest memories—and part of what drew me to that inky canon of heroism, no doubt, was an effort to understand him. Or the part of me that was him.

Of course, after twenty plus years in Brooklyn, I’m so much more sophisticated, really just about the smoothest cosmopolitan you ever did—well, look, no matter. No matter how sophisticated and wide-ranging and Zelig-like in my (mis)adventures I could ever aspire to become, Annie has me, and most of the rest of us too, beat in how much color she has found in her life and career, how many hats she has worn, how bold she has been, and how at ease with herself she is and with what she has accomplished and continues to accomplish. She is an excellent person to talk to if you’re interested in thinking about the best conditions for engendering creative community in an urban setting. And, yeah, specifically, as pertains to recent bohemian cultural history in New York City, with instructive recollections for the present and to provide a sense of perspective on what all has changed.

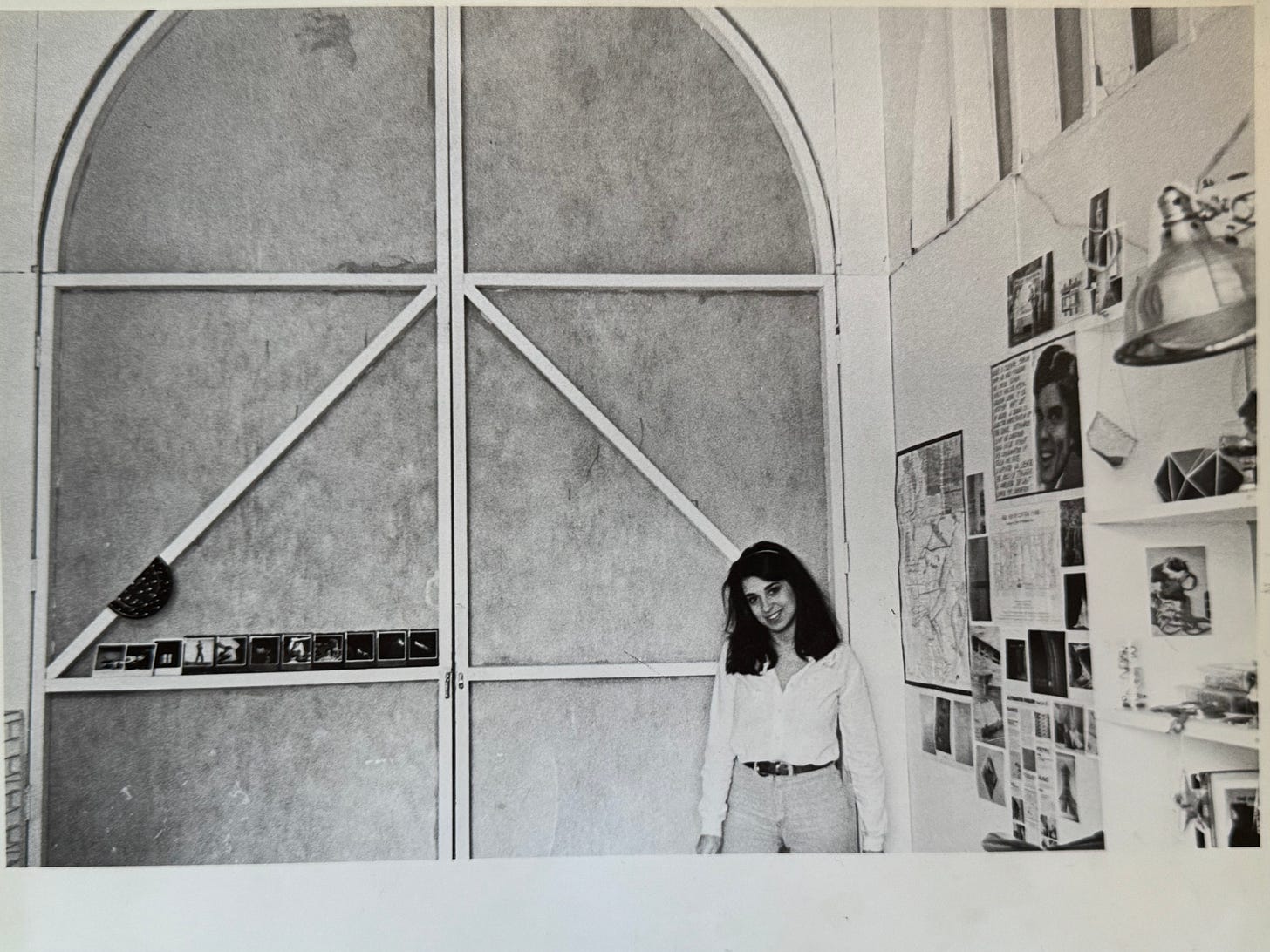

In the early spring of this year, Annie and I met up at her loft in Tribeca. We started to talk, then time started to dilate, as it sometimes can, when the convo is right.

JTP: You’ve lived in New York for a while. You’ve had some colorful mentors.

AN: Yeah [laughs]. Mentors feel like kismet. Every person you meet can knock your life in another direction.

JTP: When did you arrive… Your early to mid-20s?

AN: I was 21, or 20. It was the ’80s. I got a room in the Coogan Building, which was on 26th and 6th. Historic building that tragically the city tore down. The Coogan Building was the first men’s club in Manhattan. A sports club.

JTP: Like, in the 1800s?

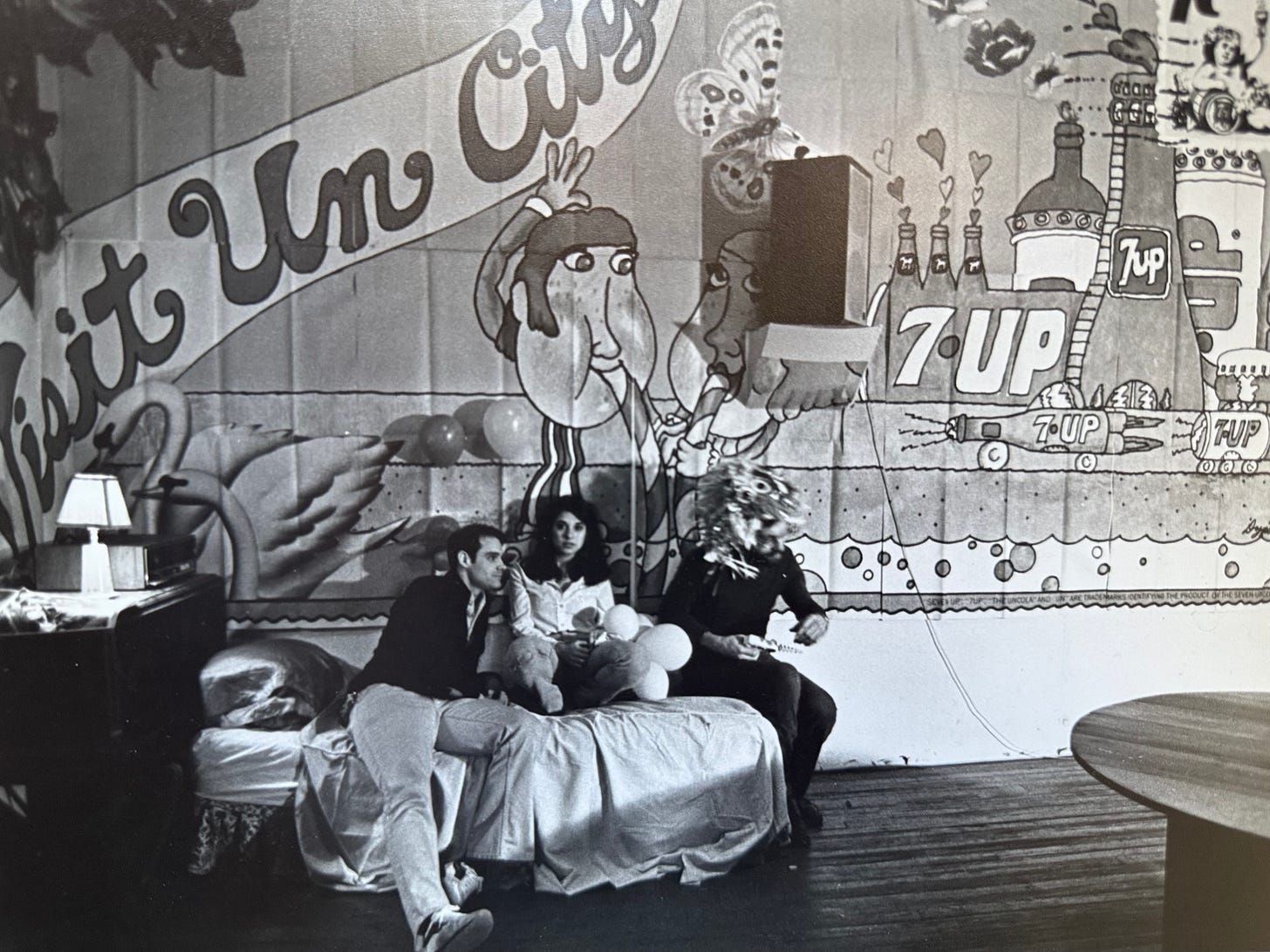

AN: Yeah, and so we moved into a converted tennis court. Our bedroom doors were giant. The guy whose loft it was, he built things for TV commercials. This is pre-CGI. For instance, he had to do a commercial for Honeycomb cereal. So he built a honeycomb that was probably as high as this ceiling. [Gestures upwards within her spacious and bare-boned loft.] The kids in the commercial, their heads could pop out of the honeycomb holes.

JTP: I think I probably saw that commercial.

AN: Yeah! He built a printing press for one commercial, a King Kong for another. There were all these big props in this big place. He saved Tropicana cans and made domed chandeliers out of them. He was always coming up with something new. How you lead your life impacts on who you become. To a lot of people, it would be a crazy choice to go live there. But to me it was cool. A place with creative people. I had a big portfolio of art and needed a place to stretch canvases and paint. When I left that loft, I moved into a former methadone clinic in the East Village. It was in the basement of a defunct hospital. My bedroom door had glass with metal wire in it, so that if somebody punched it, it wouldn’t shatter. And the windows were the sliding nurse windows for when you hand the methadone in and out.

JTP: A defunct methadone clinic.

AN: Yes, there weren’t people coming in and out. And then I moved into a meat locker, which was in the old Area building. Area was a nightclub back then, and my apartment was an old meat-locker from before they had refrigeration.

JTP: So, no windows.

AN: No windows. The bedroom was a walk-in freezer. Huge wooden door. I remember I had to keep a shoe in the door because I was always afraid if the door shut while I was in there, how would I get out?

JTP: Pre-cell phones.

AN: [laughs] Yes. The meat locker was made of layers of wood and metal, to keep the blocks of ice cool. I used to think of it as an orgone box. Because Wilhelm Reich’s orgone box was made of layers of organic and inorganic matter.

JTP: Did you start to feel differently?

AN: [laughs] I don’t think the orgone box worked at all. But how would I know? Maybe it did.

JTP: What came next?

AN: I rented this place, in an Alexander Calder building. It was just a raw space. There were no interior walls or ceiling. Big holes in the floor with oil spills, or something from the old machines. I think it used to be a cheese warehouse. And I have no idea what all the machinery or metal was for. I always assumed it was maybe to make his sculptures. Anyway, to bring it back to mentors—luck, kismet, happenstance, intent, what brings you to who you become? Calder was dead by the time I got this place, but he was a mentor in a weird way, in that his family legacy believed in cheap spaces for artists.

JTP: So you were a painter?

AN: That’s how I came to the city, as a painter. That’s one of my paintings up there [gestures to wall], that sort of dragon underground, coming up.

JTP: Is that from back then, from the ’80s?

AN: Yeah. So, you have people who they will never know how much they meant in your life. Alexander Calder will never know how much he changed my life. Because I was able to rent a cheap space to make art. And that’s also because Mary Calder, his daughter, passed on that benevolence of the arts, and an understanding that artists need space. Most people don’t know that about the Calder family, but if you’re a descendant of Calder, you know that.

JTP: Are you the only person in the building who’s still here from that time?

AN: Everyone else is gone. There was a potter on the first floor. A jeweler on the fourth. There was a music studio. All artists. Suzanne Vega, the singer, her band lived on the 3rd floor. They used to practice there. What’s the ontological thing? Does existence precede essence, or does essence precede existence?

JTP: Chicken and the egg.

AN: If you chose to live in a tennis court, then a methadone clinic, then a refrigerator, then a cheese factory, how does that impact on your life? When I’m staying in a normal apartment, I’ll think, ‘Wow, this feels safe and clean.’ Back then, this loft was a disaster zone. One of my friends came in when I was thinking of renting it, and they said, “Annie, pigs wouldn’t live here.” [laughs.] Holes everywhere. The only things here were a toilet and a motorcycle.

JTP: Yours?

AN: No, some guy came and took it away at some point.

JTP: Well, now you have this cutting edge technology [pointing at boxy-style television from the early ’90s]

AN: Yeah, that TV’s 30 years old. TVs are impossible to get rid of in New York. You can’t just put them on the street.

JTP: Well, I’ve got a car, if you ever—still works, though?

AN: No. It’s a dead thing.

JTP: But it looks right in its place. What would you put there if you removed it?

AN: Books. Obviously. Thousands of books. [laughs] We could take it and throw it off a bridge.

JTP: Yeah, we could do a little Cocksucker Blues.

AN: Cocksucker Blues! We could just toss it out the window.

JTP: Make sure no one’s down there first. Important safety tip. So you got here, you wanted to be a painter. You had like a show or two…?

AN: I took my portfolio all over the place and couldn’t get anything anywhere. Because I think my work wasn’t clean enough for graphic arts. I went to some of these agencies… Back then there was Grey Advertising, I worked there. Places where you could do paste-up and mechanicals for ads. You needed a good design sense.

JTP: Hopper-esque.

AN: It was more a matter of being OCD. Back then you had paste-up and mechanicals, where they used to lay things out with a pot of glue and a brush. You’d glue the images down with rubber cement, then you’d do the calligraphy, then you’d have vellum layers, gels, to get it photo-ready for a magazine ad. Archaic compared to what they do now. But fun. I took my paintings, lithographs, and zinc etchings around to galleries. I just couldn’t find one for my work.

JTP: You weren’t clearly participating in this movement, or—they couldn’t place you—

AN: It was the rise of the SoHo scene, like Gagosian, Mary Boone, all those big galleries that were exploding. With artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle. And that wasn’t me at all. In the ’80s the East Village art scene was a big deal. I would have fit in better there. But… before that could happen, I had gotten my job at Marvel.

JTP: Was this a year or two, the time when you were looking to make it as an artist?

AN: A year. Then I got all those jobs you can get as a young girl. When you’re young, a lot of doors open. You don’t even have to be beautiful. I did modeling jobs, I did catalog modeling for nurse uniforms. I’m no ‘model’ model. But there are certain places where you can go and get paid to model where they want more normal-looking people. I look like I could be a nurse, so, I could do the nurse catalog. I was like a hundred pounds, so I could wear anything. I was an artist’s model. At some point, pretty quickly, you realize that all this work that just has to do with what you look like is tiresome. The work itself is boring. Modeling is so boring.

JTP: You’re being quite literally used. There’s nothing to aspire to except…

AN: Money.

JTP: And there’s nothing to build up to… You’re an artist’s model, but as soon as the artist wants to get another model…?

AN: You very quickly go, This is a zero-sum game. You’re just going to get old. I was making a lot of money, because you get paid well to do these kinds of jobs. Then I answered an ad in the Village Voice that said Editorial Work. And that was Marvel Comics.

JTP: Just ‘editorial work’?

AN: Just editorial work.

JTP: You were a reader of books? To respond to that ad confidently, what experience did you have?

AN: None. To put it another way, if we want to talk about invisible mentors, another person who inspired me was Henry Miller. I was reading a passage in one of his books, probably Tropic of Capricorn… where he was working right here in Tribeca at the Western Union building. And he used to call it the “Cosmodemonic Cocksucking Corporation” building or something, and he had some kind of horrible job that he stuck with for years while he wrote. One of his books opens with “I’m thirty-three years old, age of Christ crucified, a failure in every sense of the word.” And in one of the passages, he wrote about how he’d look up at all these skyscrapers and wonder why he didn’t have a big job in a penthouse. So one day he went into one of these buildings, rode the elevator all the way to the top. He walked into some penthouse business office, and talked a blue streak. He didn’t get a job… but it was important to him to have busted that move. So… when I went up to Marvel Comics… I didn’t know anything about comics. I honestly was not—I know it’s weird—but I wasn’t even that cognizant that there were monthly comics. As kids we had Pogo, Dick Tracy, the Sunday funnies, but when you’re growing up in the ’70s in suburbia, there were no comic stores.

JTP: Maybe at the pharmacy on the magazine rack…

AN: I don’t even remember having that. So I walked in, there were big cut-outs of Spiderman and Captain America and I thought, just like walking into that tennis court, you start to recognize places that you should be. As opposed to places you shouldn’t be. Like when I was at Grey Advertising you had to dress perfect, but I always had runs in my stockings, I always carried clear nail polish to stop runs, I carried tape to get all the lint off my crappy clothes. You know there’s something irksome about the idea that you have to stay perfect every day for a stupid office job.

JTP: You felt like you were going against the grain of the place—

AN: Yeah, like I was going against the grain of who I am. You learn to recognize environments that you’ll thrive in. As soon as I walked into Marvel Comics and I saw all the people in the bullpen, and they were pasting up the word balloons and inking and coloring and I went, Cool, I’d like to be here. Then I walked into the editor-in-chief’s office, a very nice man named Jim Shooter, and I talked a blue streak inspired by Henry Miller. Just faked it. Like, I talked about Warhol and Lichtenstein and pop culture and Pop Art because I was vaguely aware that this comics medium was being exploited by the high arts. I don’t think I said anything particularly interesting… except my energy… and I got hired to be his secretary. They would call that an assistant editor now. You’re typing up memos but also doing a lot of other stuff. And I realized, Don’t be good at a job that you don’t want. And so… I was not a good secretary. Because the work was boring! My boss figured out really quickly that I wasn’t gonna last long, so he moved me over to be an assistant editor working with an editor, and then I became an editor.

JTP: You were sick of the modeling stuff and wanted to do something more substantive, or something more related to what you were capable of doing—but what was it that primed you to go, ‘I can do editorial work’? Was it that you thought you could do anything? Or that you were a reader?

AN: I was a little bookworm when I was growing up. I read everything. All the philosophy books. All the literature. And also because I had studied film in college and it’s a visual medium, comics. Right away I was like, Oh, this is storyboarding. When I was young I had a Super 8 camera and made a film. So I think it’s like, to bring it back to something universal, When you start to figure out who you are, you need to be in environments that feel right to you, where they appreciate you, rather than butting heads.

JTP: I know there are, from having been in New York for twenty years, these theoretically in-demand jobs, or fields, where sometimes, maybe there’s a boss who can be difficult as a winnowing mechanism almost, who makes you feel like you’re going against the grain, and then when you stick it out—I mean, it’s different for different people and what they’re willing to tolerate. But the question becomes, How much do you want to be here?

AN: To create a sense of friction while hoping to inspire the person.

JTP: Not even necessarily as benevolent as that. I’m thinking, too, I was in Hollywood for six months, and there are all sorts of stories where people can be very difficult to assistants as a way to test someone’s mettle, or just underlying pathology. There’s that violent satire, Swimming with the Sharks.

AN: Well, when I was doing cocktail waitressing I worked in this place in the early ’80s called Green Street Jazz Club. The whole place was run on cash and cocaine. And the waiters were so mean to the customers. I’d be like—I’m generally just nice to people—and they were like, ‘If you want good tips you can’t be so nice… You’ve got to be a bitch.’ And I’m like, And that works? And they were like, ‘Oh… yeah.’

JTP: [laughter] Coke culture? Everyone’s a little on edge, everyone’s a little frenzied…

AN: It’s like you said: to create a sense of friction to get what you want, and that’s what some of these waiters were like: ‘Oh, yeah, we treat the customers like shit. They tip so well when you do that.’ And I was like, OK, that might be true for you, but I don’t want to go down that road. I don’t want to become a bitch for tips.

JTP: How long before you were writing comic books?

AN: A couple of years.

JTP: And you were really early as far as being a woman in that field?

AN: There were women in the underground, like Trina Robbins. And Marie Severin was in the Marvel bullpen when I got there. She came out of EC Comics. And a few female writer/editors like Louise Simonson and Jo Duffy at Marvel. There wasn’t direct mentorship at Marvel, but you were given the opportunity to learn by osmosis. Everybody’s working very hard, it’s chaotic, you learn by looking over people’s shoulders and learning very quietly. Nobody sits down and gives you a lesson. But you learn. Because we were talking about the craft all day long. I worked with Marie Severin, who I loved. She was too crazy-talented and ornery to mentor anyone in a traditional sense. But she was kind. And we did some comics together.

JTP: Was just seeing how she operated a type of mentorship?

AN: Yeah, Marie Severin would have been, like, thirty years older than me. First wave of women in the comics industry. Marie Severin did this story in a Marvel comic about me. So this is her version of me. [shows a comic featuring an Annie Nocenti-looking character who seems to have two dramatic sides to her persona, like Jekyll and Hyde.]

JTP: A little back of the book kind of thing. ‘Story by Ann Nocenti.’

AN: Yeah, we did this together.

JTP: [reading] “Dreams of Glory.” She’s drawing you. As, like, a little girl.

AN: Power-mad. That’s kind of what I looked like back then.

JTP: Besides Marie, were there a number of women at Marvel?

AN: There were more women working in the underground comic scene, like Aline Kominsky and Linda Barry, because, in general, women were more welcome in the underground. Louise Simonson, I worked for her, and she taught me a lot. She was the writer/editor working in the X-Men office. Again, you learned the skill of looking over someone’s shoulder while they worked. So the art director John Romita would be going over the layouts with some young artist, and you’d just listen and watch how he corrected every panel, and corrected the storyboards, and you’d learn that. Then you’d go watch Marie Severin or you’d watch somebody color, and you’d learn that. So I became a colorist, I did paste-up and mechanicals again for Marvel.

JTP: I guess I didn’t realize that you were doing illustrated work as well as being a writer and editor?

AN: Not the illustrations but coloring and paste-up and mechanicals. Getting physical with the artwork, yes, but not drawing. The drawing is so hard in comics, and I’m just not that kind of artist. You have to be able to draw anything on demand, from any angle, moving through space… Mundane stuff, cosmic stuff. You have to have mad art skills. Do it fast too. It’s a highly specialized skill. And underrated and under-recognized as an art form.

JTP: So who else, speaking of mentors, would you single out within the comic book village?

AN: Denny O’Neil, absolutely. Denny O’Neil was a journalist… Denny and I both wanted to be real writers. So, he was the one who said, ‘You have all these interests, you have all these political/sociological drives. Put it in the comic.’ So that kind of became my M.O. in writing comics. There was always some kind of social justice story.

JTP: What are early examples?

AN: Well, my first regular book was Daredevil. Daredevil lived in Hell’s Kitchen. He was a lawyer. I used to go up to Hell’s Kitchen and wander around and sit on benches and eavesdrop everywhere, take notes on everything I saw, and fold it right in the comic. And John Romita Jr., who was the artist, he would also just look around the streets and see things and come into my office with a drawing of someone saying, ‘I don’t know who this guy is, but I think his name is Shotgun and he’s got this look, and he wears this.’ So I’d put him in the comic. We were very in tune. Because we’re both lapsed—well, Johnny might still be a Christian, but I was a lapsed Catholic. Daredevil’s a lapsed Catholic who is haunted, perhaps, by belief. And so Johnny and I were very well-suited to take on things like Mephisto in hell. And do multi-issue epics about Who is Satan if there is a Satan? And what does he consider to be the height of evil? And I remember we did this story about how when the Devil walks into a room he brings out the worst in everyone. People start to bicker, they get jealous, they get envious, they get mean. Literally our story was all about how that’s all the Devil is. He’s closer to, like, an imp who brings out the worst in everyone [laughs].

JTP: Did you guys brainstorm that? Late night, drawing on your childhood and experiences of being a Catholic believer and how you personally understood this stuff… Was it a mutual ‘talking out’ or was it just like…?

AN: Johnny and I were always talking ideas. We had just done an epic in hell, a season in hell…

JTP: And when you say ‘season’ you mean two or three months [i.e. two or three issues]?

AN: Yeah, something like that. And Johnny came up with this idea where he’s like, ‘Daredevil’s the devil, he wears a devil suit. What if he had a beer with God?’ And that turned into “A Beer with the Devil.” Which was a story that went on to have some recognition, because it wasn’t a superhero story. It came out of something in Johnny’s life. He added in a Cain and Abel thing of two brothers who hated each other.

JTP: Is that the story you did where Daredevil ends up in a bar, it’s Christmas Eve and…

AN: Yes. So I had been dating a guy—my college boyfriend and we moved down to New York at the same time. I was in the tennis court. And he got a job in Philly. We split up a few days before Christmas. And I realized, I have nowhere to go. I mean, I didn’t have nowhere to go—I could have called anyone up, or even my own family, and done Christmas… But I kind of liked the idea of just being alone on Christmas. The bar downstairs, a couple of blocks south, was Billy’s Topless, which was an infamous down’n’dirty topless bar. Chelsea was an interesting neighborhood. Aside from having the first men’s gym, it also had the very first swingers’ bar. Back when they had things like key parties. Remember key parties?

JTP: The Ice Storm, Rick Moody.

AN: The Ice Storm, yeah. Because these were things that people were doing at the time. New York had Plato’s Retreat, had the sex clubs. So I went into Billy’s, and I had the most amazing Christmas Eve with a whole bar-full of people who had nowhere to go.

JTP: In the comic book it isn’t rendered as a topless bar…

AN: No, because Marvel…

JTP: Right.

AN: And that wasn’t the point. The point was the people who would end up at a place like that on that night. So, Johnny and I had a lot of fun creating stuff. For instance, in the ’80s everybody was afraid of nukes. Johnny and I came up with this little kid Lance who had built himself a fallout shelter because he was so terrified. But really what he was afraid of is that his father was going to blow up. His father had anger issues. So you have an explosive father, whose name was Ammo, and we turned him into a supervillain. Basically, you always want to reduce things to something understandable—like a son afraid his father’s going to blow up… conflating that with the fear that the world’s going to blow up. Then you’ll have an interesting little character. [laughs] And Johnny had a sensibility that he was game for anything.

JTP: That’s cool. You talked about being in this industry, then longing to be ‘a real writer.’ Pinocchio-style. Did you have mentors in that respect? People who you looked up to? I don’t know if Gregory Corso would qualify…

AN: He was a mentor in the ’90s. The ’80s I spent at Marvel Comics. I quit in 1989. It was stupid in a way, but sometimes you have to do stupid things. I had just started to make a lot of money at Marvel. And I walked away from that. Sometimes you have to walk away from money. Because it can be a trap.

JTP: There were frontiers you wanted to explore beyond your own professional experience at that time?

AN: Yeah, I went back to college, to Columbia, for my masters. And they had internship programs. So I got an internship at a magazine called Covert Action. Again, I considered them mentors—Ellen Ray and Bill Schapp. You always think at an internship they’re going to have you Xeroxing and running errands and getting coffee, but they were just, like, ‘Write! Edit!’

JTP: They threw you right in the fire.

AN: Right in the fire! The magazine was created with Philip Agee, who was a whistleblower on the CIA. So the magazine chronicled the crimes of the CIA. And they published Lies of Our Times, which chronicled the lies of the New York Times. A cool job. You’d get into the office, you’d open the New York Times and go, ‘That’s not true! Let’s write about that!’ Mostly it wasn’t lies so much as long-entrenched biases about certain areas of the globe.

JTP: An obviously red-hot example right now would be Gaza. You see on social media all the time, Oh, look at this distortion of language that they’re using to not say… ‘Occupied Territory’ or whatever.

AN: So, yeah! That’s the kind of stuff we would do. We’d find entrenched biases and point them out. It was kind of newish field called ‘media criticism.’ And so, these are just acts of generosity that are handed to you. The Calder family believing artists should have space to make art. The editor-and-chief of Marvel realizing that I knew nothing about comics but hiring me anyway. Because I had the right energy, I guess.

JTP: Vibes?

AN: Vibes. [laughs] And then Ellen and Bill who didn’t believe in making an intern do the grunt work. They treated me almost like an equal right away. Which was astounding to me. And that’s a lesson you learn: Just because you’re the boss doesn’t mean your intern isn’t your equal. That impacted on when I had my own magazines, like Scenario, I always treated the interns the same way. You wanna write? You wanna edit? You’re not just the Xerox-er. Yes, you do have to do some Xeroxing. Because [laughing] I don’t want to do it.

JTP: How long were you at Lies of Our Times?

AN: A couple of years. And then I worked at Prison Life. I met a couple who were both ex-cons and had a magazine about, for, and by convicts. No one knows what goes on in prisons. There’s a wall around them and no media allowed in. And so Prison Life allowed people to see what goes on right from the prisoners’ mouths. It’s weird because that was thirty years ago and the conversation around prison is the same. Taxpayers pay for other people to make a lot of money by incarcerating people for nonviolent drug offenses.

JTP: Was it the social justice angle that drew you to that? You met this couple and they had been prisoners, but… had that been an interest of yours before?

AN: They opened that door. I probably never even thought about prisons before. They opened the door. The conversation, it’s the same conversation. There was just some big article about ‘Are prisons really for rehabilitation or punishment?’ They’ve been saying that forever. Way back to Tocqueville, when he came to the United States and was horrified by the incarceration. And what did he say? Something like, ‘You know a people by how they treat their incarcerated.’ Because people have resentment, ‘He committed a crime and now he’s getting three hots [hot meals] and a cot, and an education?’ What people don’t understand is that context is everything: he didn’t have opportunities. He didn’t have an education. When you get out—everyone gets out of prison, or at least most people do—why not have them learn a skill? The recidivism rate is high… because they haven’t learned how to be a carpenter or a plumber. They didn’t get to study or get a degree. People used to get out of prison with more opportunities.

JTP: Did you get close-up type knowledge in working at the magazine? You were running it, or you were editing for them, or writing?

AN: Richard Stratton and Kim Wozencraft, the couple I met, they were the editors. I wrote stories for them and interviewed people. I was there for a couple of years, maybe. After that I started writing screenplays. And I sold screenplays. I got a film made. My friend Roland Legiardi-Laura and I started ‘The Fifth Night’ which was a staged live screenplay reading every Tuesday night at the Nuyorican Poets Café. I was the script editor and we fully cast them. They were huge fun and a huge education in what works and what doesn’t in film. From there, a guy who used to come to the readings, Tod Lippy, he was leaving Scenario to start his own magazine… I think it was called Public Fear… Then he went on to do Esopus Magazine, a high art magazine. Tod used to come to the readings, and he basically said, “I’m leaving this job as the editor of a screenwriting magazine. Will you come in and interview for it?” I got that job. I spent the next seven years going to Sundance and film festivals, and interviewing directors and filmmakers and screenwriters.

JTP: So it was during this time, going to festivals, interviewing filmmakers, that you started writing your own screenplays?

AN: Yes. It was such an education. I interviewed great directors, great auteurs, great artists of all kinds. And… it was interesting to see how people treated me. For some filmmakers it was just an appointment and you did the interview. And other people were like, ‘Well, who are you?’ Scenario’s how I became friends with Francis Ford Coppola. He ended up giving us some seed money to start a film school in Haiti.

JTP: OK, there’s a ‘film school in Haiti’ chapter in your life, too?

AN: My friend David Belle, I visited him in Haiti in the early ’90s. He had just bought or rented an old coffee warehouse. Jacmel, Haiti, looks like Tribeca or the Meatpacking District. Big warehouses for spices, coffee. And this was a giant coffee factory. This was so long ago, there were no cell phones. David had just gotten a landline. He was so excited about that, and said, ‘Now that I have a landline, I’m going to start a film school.’ I said, Really? Then he said, ‘And if I do, you’re going to come down and be my first teacher.’ And I was like, OK, David. A few years later he called and said, ‘Come on down.’ So we taught film in Haiti.

JTP: And that was also a couple of years? You were here and you were there?

AN: Yeah. And Francis Coppola, he’d tried to start a film school in Belize. So he knew how hard it was to do such a thing. And he has the right magnanimous personality to say, “Of course I’ll help.” As opposed to a lot of people who just wouldn’t—they’d be like, ‘Yeah, good luck!’ But he’s been a pioneer his whole life.

JTP: What did you think of Megalopolis?

AN: I haven’t watched it yet, but I’m gonna. I’m excited to.

JTP: Watched it, and just saw Apocalypse Now Redux for the first time. And this is obviously sort of a tangent but I would make an argument for Apocalypse Now being the greatest film of all time.

AN: I agree with you there. And I also really like Hearts of Darkness [the documentary made by Eleanor Coppola about the making of the film]. So… it’s kind of like everywhere you go you meet people who really know how to live life. And they know how to live life, but they also take a lot of risks. Around 1990 I met Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsburg, Bill Burroughs, and Robert Frank and June Leaf.

JTP: And that was when you met Barney Rosset as well? All a little coterie?

AN: Yes, Barney Rosset didn’t have that much to do with the Beats, I don’t think…

JTP: Well, but the obscenity trials… Barney Rosset was a publisher for William Burroughs.

AN: Oh, yes, true. And also Henry Miller. So they probably all knew each other. But I didn’t know Barney in that context. I used to just go over there and shoot pool and talk to him and Astrid. I vaguely remember one time we went over and did an interview with him because I had also met Norman Mailer, and became friends with some of the Mailer family. Again, these are people who have a rarified understanding of the world and therefore, there’s very little bullshit, very little chitchat. These are people who want to get to the essence of life really quickly, conversationally. You could not have a conversation with Norman Mailer or Gregory Corso or any of these people that would be mundane.

JTP: Right. They would be like… ‘Bye.’

AN: Or… they would go somewhere deep fast. Also because everybody was thirty years older than me, they had a curiosity for young people. The idea that people who were twice my age were interested in me said something good about them: they were interested in what young people had to say. I guess I’m still mystified by why some people took an interest in me. But they did. So I spent a lot of time hanging out with Gregory Corso. Who taught me a lot. Because what he recognized was that I was kind of an uptight, repressed New Jersey girl. Because I was raised in suburbia. In a fairly religious conservative family.

JTP: I’m from suburbia too.

AN: So you know what I mean! It’s like you have these little windows into the bigger world through books—art books and literature. But you’re in isolation from it. So you crave it. And my family life was really nice. My parents were really smart. We had good conversations and—but there was always this kind of suburban, I don’t know if I want to say ‘repression’ so much as that thing where you end up someplace where the lawn is manicured and everybody behaves a certain way and nobody draws out of the lines in the coloring book and you’re just very indoctrinated. So I think I was kind of uptight and nerdy and bookish—

JTP: Even after a decade in New York?

AN: Oh yeah. Comics were not cool in the ’80s. It was a little nerd club. Marshal McLuhan said something like, ‘Give me your kid at X years old and I’ll return them to you changed.’ It’s sort of like, that early training sticks with you. And that Get up, go to church, go to school every day, do your catechism, mow the lawn, do everything normal… the origins of the United States school system were based on factories. And there were bold statements made by the people who created the school systems, saying, ‘There will always be an elite who will go to college. But for most people they will go into the factories.’ The school bells, every hour you’re interrupted from what you’re learning. That whole indoctrination to make a good citizen who’s going to be a cog…

JTP: Dickens has a novel about this, right? Hard Times? So did you have models who you were looking up to? We were talking about mentors or invisible mentors… Did you have anyone whose path you were emulating? Because you were never on a straight shot, clear path: you came to be a painter, then you were in comics, then you were doing magazine-writing. Did your ‘self-model’ change, the people you might look to emulate, depending on where you were and what you were doing?

AN: I was just lucky that I met these great humans.

—> Pt. II will appear in about 10 days.