"Learn by Doing": A Convo with Annie Nocenti about Superheroes and Mentors, Present and Invisible, Part II

Incl. Alexander Calder, Marie Severin and the Marvel Comics bullpen, Henry Miller, Francis Ford Coppola, Harold Channer, Robert Frank, June Leaf, and Gregory Corso

read Part 1 of the interview here. Or visit Ann Nocenti’s website.

AN: So, like, Gregory Corso: he used to have a blast embarrassing me in public. Because I was one of these people who was trained to keep a certain amount of decorum in all situations. And Gregory was the opposite. He would blow social conventions apart instantly, watch me squirm, then say, “Now you’re getting it, girl!” I wrote about it for a magazine called Longshot, and another story for Stop Smiling. A story about Gregory. Gregory would ride the subway. Most people are quiet on the subway. Same with elevators. When you go places with Gregory Corso there’s no way he’s going to be quiet. He’s going to start some kind of circus. He’s going to start yelling at somebody, testing everybody, really. Some people thought he was incredibly obnoxious. Like, a troll. Some people couldn’t stand him and didn’t want to hang out with him. For me, I like to be with someone who’s blowing up conventions all the time because it was something I instinctively wanted to do but couldn’t. Gregory was state-raised. He went from reform school to foster home, foster home to jail… He was a classic state-raised kid. So he came from the opposite background than I did.

JTP: He was one of the seminal figures of the Beat generation, but when you knew him, he wasn’t living large or anything. It isn’t like he made a bunch of money.

AN: No, no, no, no. I don’t think any of them did well, or maybe—I don’t know how any of them did financially. You have to remember that they were junkies. So, William Burroughs, Herbert Huncke, Gregory Corso, they were living shot to shot. In some ways, Gregory’s poetry speaks to me deeply. Because he was doing something that maybe Shakespeare and Dickens did. He was merging the language of the street with more of an Elizabethan Shakespearean thing—he was creating these literary buttresses at a high, high level, and also mixing it with street language. That’s one of the reasons I love the TV show Deadwood, because David Milch was doing something similar to Corso. A populist impulse merged with a classical architecture.

JTP: Corso, did he tell a bunch of stories? Were there things you’d ask about? Or was it more just living in the moment?

AN: We were more just living in the moment. But I do have huge regrets that I didn’t, like, literally tape our conversations or something. Because some were just extraordinary, out there.

JTP: Would you consider Robert and June to be mentors as well?

AN: They just brought me into their world. Who knows why.

JTP: In what manner do you think being a part of their world influenced you?

AN: I found in them a like-mindedness. But also just the chaos of making art. June, in her studio, she was always making mythic beings. There was a decade where we went everywhere together and we spent holidays together. Especially when Pablo, Robert’s son was still alive. I remember we were in Cape Breton, and June and I decided to take a road trip to the Alexander Graham Bell Museum to see his ear devices. Bell’s wife Mabel was deaf, and she inspired him invent hearing devices, and eventually the telephone. June became obsessed with building me an ear, because I have only one working ear. And my partner in the ’80s…

JTP: What does that date back to?

AN: Sixteen, a horse-riding accident. I cracked my skull. My partner in the ’80s, Armand, we lived together on Wooster Street. Big empty building. And we had a 13-foot boa constrictor, we had a Great Dane, a macaw. We had all these big pets. And he built me an ear-horn.

JTP: How’d they get along? The Great Dane and the boa constrictor?

AN: Well, they were kept separate. Although Armand used to drape the boa on me, for sure. I have photos of me somewhere, naked with the boa constrictor.

JTP: You were writing comics? This was during your comics era?

AN: Yeah, writing comics.

JTP: It’s just so funny, because you’re talking about how, ‘Well, I hadn’t broken down my suburban uptightness’—but maybe that just means more at social mores?—cuz then you’re like, ‘And I was living in this abandoned building, naked and draped with a boa constrictor. But you know… I was pretty uptight!’

AN: Yeah, yeah, exactly [laughs].

JTP: That already seems so wild for a more conformist mindset. Even knowing that you lived that experience as a comic book writer in the ’80s. Already that seems like, ‘Oh my god,’ beyond, you know, the horizon of what a lot of people would imagine or whatever.

AN: But I do think even though you get the kind of timid uptight repressions that are baked into a suburban Catholic upbringing, you do have a secure place that you’re springing from. There was no abuse in my childhood. There was no trauma. These things are important. Whereas I kind of got to a similar place to what Gregory Corso got to, or we at least were like-minded in certain ways. But he came from a childhood of extreme abuse.

JTP: ‘A similar place’ in the sense of radical openness to the world and experience and…

AN: And no matter how you get there… you don’t have to get there, but if you get there, that’s good. You somehow get to a place of—what you said, radical openness.

JTP: Is that your hope for the world?

AN: It’s not for everybody, for sure. Every time I had a job that paid money I’d find a way to quit to do something else! I left Marvel and I had the series of magazine jobs. The years when I was writing films, I had an agent, and my agent was like, ‘Come to LA, I’ll get you in to meet everyone.’ And I just didn’t want to do that. So there were points in my life when I was like, Should I stick to this and make the cash? And I always chose not to. Of course, there were a lot of lean years. It’s not bad to have a lot of lean years, because you should know what it’s like to go into a grocery store and wonder if this can of beans versus this jar of peanut butter is the cheapest way to get you the protein you need. Living close to the edge is a good way to understand the universe.

JTP: You started off and said your comic book writing and what you were known for—having a social justice motif, something you kept coming back to—looking back from our present day, when now the whole ‘social justice warrior’ paradigm…

AN: Well, now it’s a bad word. It became a bad word.

JTP: The social media performance of these things. Do you look at that and go, ‘Hell, yeah!’ and at the same time maybe, ‘Ehhhh.’

AN: My feeling is ‘hell, yeah.’ When the whole idea of the social justice warrior became a bad thing, that started with a certain level of elitism and misogyny too. The Gamergate and Comicsgate harassment campaigns, when these weird sensibilities burned through the arts and tried to take down women in the arts, the NEA, burning books, all this stuff: it’s one of the forces that undermines our society. The comic book industry fell apart in the ’50s because this guy Frederic Wertham wrote a book called Seduction of the Innocent that claimed comic books were ruining youth.

JTP: That’s an earlier era, right? Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay draws on that a little bit?

AN: Yeah. And you can’t deny the authoritarian fascistic nature of a superhero. That is the weird thing. When people were coming after me online, like, ‘Oh, she’s a social justice warrior, fuck her,’ you know. Some people who were my fans, or just smarter, would post the image of Captain America punching Hitler in the face, made by two Jewish kids in 1940, and say, ‘What are you talking about? Comics have always had social justice angles.’

JTP: There’s something arguably subversive—look at Superman. Talk about Triumph of the Will and the ideal Nazi strongman and here you have these two Jewish boys who take what they’re doing, but this new character is standing up for, notionally, the right things, even though he’s taking your fascist paradigm of a strongman capable of doing anything, and flipping the outward meaning.

AN: Well, they’re definitely power fantasies. Superheroes are power fantasies. I think if you look at the mutant heroes, the X-Men, they were to help marginalized kids who felt like they didn’t fit in. We all know that. When I went to high school in New Jersey, the blond blue-eyed cheerleader and football player, that was the top of the heap. Then you had the weird little nerds making art in the corner, which is where I was. But I was one of the darker-skinned kids in my school. I used to get called “guinea wop” all the time. Prejudice against Italians was there, for sure. Then you have the opposite of that, the power fantasy thing, and the escalation narrative of comics where everything is resolved in a fight. There’s always been that kind of creepy feeling when you’re making superhero comics: yes, action adventure and a good yarn. Everybody wants an escapist action adventure, fine! But the superhero narrative puts the heroes at a genetically superior place.

JTP: A character like Daredevil is interesting in that sense because he’s—

AN: Handicapped. He’s blind. He still busts the norms in that, yes, he’s a lawyer, yes, he’ll fight you in court. But if he loses in court, he’ll use his fists. There’s been a lot of creepy stuff in comics where they border on being fascistic or too authoritarian. Or government-approved. Iron Man, the billionaire playboy.

JTP: Elon Musk, right? And I don’t know if you saw this, but during the recent election season, the presidential campaign, I would see—and I grew up with Star Wars being the big movie franchise that really galvanized the popular imagination of the young people, like Greek gods or something, it just felt so important when I was a kid, emotional and powerful. And maybe the Lord of the Rings series, the Peter Jackson trilogy, was that for the next generation. And then you get to The Avengers movies, and you see, globally, a worldwide phenomenon, and there are so many of them, what is it, like, 30 or 40 movies now? But that original Avengers series of movies, with this standoff between Thanos and Captain America with a broken shield. I thought it was really well-done in this big tentpole mode. Which is hard to do, because a lot of things have to go right. But the reason I’m mentioning it is that the Trump campaign—during the DNC the Democrats tried to pin on him Project 2025 and fascism and taking us back to the 1950s or even earlier, these outdated norms, and they really drilled that in for the four days of the DNC. Then, literally the next day Trump is like, ‘I’ve been endorsed by Robert Kennedy Jr.’ And they started putting out these images—I don’t even know if it was the campaign itself, or organically people on Twitter doing this—but taking The Avengers, that movie poster, and redoing it so that it was Donald Trump’s head, RFK Jr., Tulsi Gabbard, and Elon Musk, creating this pretense that ‘Oh, we’re the ragtag team of superheroes.’ And I do feel like on an unexamined level, that big blockbuster level, these movies can be so emotional for a mass audience, speaking to the child in each of us… This big feeling about the battle between good and evil. And so the ability even to distort that a little bit and make people feel like, ‘Oh, well, huh… maybe they’re the heroes here.’

AN: The Rebel Alliance.

JTP: Yeah, literally Peter Thiel after the election… Before the election he was maintaining this indifference, like, ‘Oh, if you held a gun to my head, I would vote for Trump. But really I feel indifferent.’ After the election, he sat down with Bari Weiss for this three-hour podcast, very triumphalist, like, ‘Yeah, I endorsed Trump in 2016. I saw that this was the direction that things needed to go.’ And then he cast Trump and himself and Musk and this whole coterie as the “Rebel Alliance,” using that exact phrase. Like, ‘Oh, we’re the ragtag Rebel Alliance, and the Democrats are the Empire.’ And someone might ask, ‘What does this so-called Rebel Alliance want to do?’

AN: They want to consolidate billions of dollars…

JTP: Close the border and cut taxes. Really liberational rhetoric! Yeah. This complete mass mindfuck.

AN: Anyway, I’m not as interested in talking about myself as I’m interested in What have I done in my life that can help the next kid? In terms of making their choices. My father was a teacher. I’ve been a teacher. A natural-born teacher. Can you walk away from money because you know it’s time to walk away from money? Or walk away from something you’re succeeding at doing to do something else? It’s sort of like how Peter Bogdanovich, to keep it in the film realm, he started as a film critic and used that to meet his heroes. He tracked down Orson Welles and John Ford. He met all of them. And he learned how to do impressions of them beautifully. And he used that for his own films.

JTP: Did you meet Bogdanovich?

AN: Yeah, yeah, I interviewed him for Scenario, then I did a stage interview with him too. He was funny. Directors wanted to be in Scenario. Because they trusted the magazine, because the magazine had zero personal information in it unless the interviewer gives it up. Even though a lot of the situations I was in, while interviewing somebody, there was so much that could have been fodder for tabloids.

JTP: Discretion. Respect. Was that the reputation of the publication that preceded you?

AN: Yes, that was the mentality, what the founders, Tod Lippy and Marty Fox [playwright and PRINT magazine editor] did. They started from the viewpoint that the screenplay is a piece of literature. That’s why Tod and Marty came up with the idea that the screenplay would be illustrated. As if the roles were played by no recognizable movie actor. I mean, I love this Wild Bunch artwork. [Hands over an issue of Scenario featuring the original screenplay for The Wild Bunch.] Our artist Jonathan Twingley nailed it so well. The shenanigans of actually making a movie radically change a script. So what we’d do was print the original script, then talk to the writer, or writer-director, about what had changed.

JTP: You left Scenario?

AN: It went out of business. The magazine crash of 2002. All the magazines started tanking. It was the dot.com bubble. People were putting money into all kinds of stuff, but then… During my heyday as a writer, I was getting a couple of bucks a word. All the way up to writing for Conde Nast was five bucks a word. And now, will people even pay you 100 bucks for an article?

JTP: Sometimes. Now, a dollar per word is, like, oh wow! So generous.

AN: So generous. But, yeah. That used to be the norm.

JTP: This might be a fantasist type question, but can you imagine a change in the culture where writing is rewarded again?

AN: I don’t think so, because it’s a whole new universe now.

JTP: Self-platforming is so easy…

AN: And nobody wants to pay for writing. Because there’s so much free writing online. That then leads to the deterioration of fact-checking, which leads to the deterioration of journalism, which leads us to where we are today. A world of fake news and people believing totally false shit.

JTP: The collapse of local newspapers too and…

AN: Yeah! Nobody hires fact-checkers anymore.

JTP: This is important to you because you were in magazine world, and fact-checking used to be standard there. Whereas it isn’t so much on Substack or whatever.

AN: Yeah, yeah, and I did all my own fact-checking. I trained myself, because I didn’t have any formal training, to use original sources only. Once you had Google, you would type in something and get the first hit that you would get—and people would take that first hit and think that was a source. But it isn’t. You have to go to a primary source.

JTP: With AI it’s even worse. Things can be just patently false.

AN: You have a deterioration of the normal processes. In the old days, you would triple-check. You would use three resources. But I came of age as a journalist when you had to go to libraries. I spent a lot of time in libraries researching stuff. And libraries lead you to original sources. I don’t know if words are ever going to—and we’re talking about all the arts, because there are artists who make no money and Sotheby’s auctions where things sell for millions and millions of dollars. Or this recent story where an artist bought a banana for 25 cents, then it sold for 52 million. Because he duct-taped it to a wall. I mean, these are absurdities that prove the rule. Everything is out of whack.

JTP: You don’t think there’s any possibility… because where does it lead? It’s everything: broadcast news, late-night comedy, newspapers—go on down the line, and they are all beleaguered institutions in danger of collapsing. Everything’s moving away from them. Just to this middle-man internet plantation culture where it’s like, ‘We have the big mediating platform, and you can all put your stuff here, and you may get some little compensation from this or not,’ but it’s really just about being the one who has the platform that people go to… and the artists or the wordsmiths or the news-people become secondary.

AN: And it’s also about young people. They don’t want to pay or subscribe, but they’ve also figured out how to—the emphasis now seems to be on cult of personality. TikTok your way into something interesting.

JTP: Influencers! Do you think when you moved to New York if ‘influencer’ had been a possibility then, that you might have followed that path? Concentrated on your following? Shared your endorsements and product deals?

AN: No. No, thank you. [laughs] I was never…

JTP: Maybe you could have been an artist’s model, shared some TikToks about a day in the life of a model who lives on a tennis court?

AN: I don’t think so [laughs]. Although when I was at Marvel, everybody there was so insanely creative that a bunch of my colleagues started their own TV show. Because this was in the ’80s and people were still watching TV, but only had seven channels. You had 2, 4, 5, 7. Then there started to be “cable access” channels. Dee Dee Halleck had Deep Dish TV and Paper Tiger. She was one of the pioneers of being a news videographer. When I was in college in the late ’70s, I got a job shooting for this guy Harold Channer who had one of the very first cable channels. It was an interview show. And so there’s another mentor: I said to Harold, “I don’t know how to shoot.” And he said, ‘Just do it.’ And I learned how to shoot.

JTP: This was an interview show, and you went on to do many interviews yourself. So, early training in that regard.

AN: It was funny because our scam—you had to go to 23rd Street, drop off your VHS tape the night before your show was going to air, and then it would be on TV the next day. There was Robin Bird, the porn girl. There was Ugly George, the guy who used to walk around with a giant camera trying to get girls to take their t-shirts off. There was Paper Tiger. There was Deep Dish. You just dropped your tape off, then it would air. No guardians at the gate. And so Harold Channer and I would do these interviews. He’d interview famous people, politicians and big-thinkers and philosophers, and I’d shoot it. And then at the end of the interview one of my jobs was to say, “OK, yes, I’ll be sending you your invoice if you want a copy of your show.” And we’d charge people $250 for the VHS, and they bought it. Finally, one day we were interviewing the president of NYU. And I did my usual thing, went up to him after, handed him the invoice, and said, you know, “It’s $250.” He looked at me and said, “I’m just going to tape it myself tonight when it’s on TV. Why would I pay you $250?” Then I went back to Harold and I said, “The jig is up!”

JTP: He’s destroying our business model!

AN: Basically that was it, as soon as people realized they could just tape it themselves. And Marvel Comics had this TV show called Cheap Laffs that the staff made. It’s the hilarious early cable shenanigans at Marvel Comics. Little skits, you know.

JTP: From the office place?

AN: Yeah, comedy skits.

JTP: Are these still around? As VHS or whatever?

AN: I’m in a couple of them. I guess you’d have to google it. Let’s see… Cheap Laffs, Marvel Comics, YouTube, probably. [searching the internet] Oh, here. One comes up.

[dialogue from the show] “As I was saying the point of this show is… well, there is no point. With a name like Cheap Laffs, you want there to be a point, huh?”

AN: And it goes on.

JTP: This is an early form of self-platforming, in a way. Like TikTok videos.

[More Cheap Laffs dialogue] “May I ask you a question?”

“What?”

“What is humor?”

“I think humor is a nervous response to the fact that we’re all going to die some day.”

[subject of interview then appears to get hit by car, and gag repeats over again, with different Marvel person as interview subject, and the same line, and the same gag, repeated multiple times more.]

JTP: I think now of early Saturday Night Live or something. This feels more like ’70s, ’80s skits and the writing was more anarchic? Less of a house-style, a polished mode, and more off-the-wall.

AN: Whatever they felt like doing. It was a different time. You made a little TV show. Then it would be on cable access TV. And it was radical. Because regular TV had studio productions. But there you are. And the idea that we were charging people $250 is just so… cuz we were hustlers, you know.

JTP: How long did that last?

AN: Harold Channer’s show was on for… almost 50 years. People didn’t understand in the early days—of course the president of NYU knew about it. But most people thought, ‘Yeah, that’s what it costs to get a copy of you on TV.’

JTP: You guys were doing exactly what the president of NYU said? Recording it that night and…?

AN: Copying the original tape and handing it to them. [laughter] And invoicing. Harold Channer even interviewed Qaddafi in Libya. When that aired on TV the FBI went nuts and started following him around. I didn’t get to go on that trip, obviously. It was a wild time. We interviewed great philosophers, economists. Rockefellers. Vice-presidents. Everybody wanted to be on TV. And they didn’t understand that cable was Ugly George and Robin Bird. And Cheap Laffs.

JTP: Letterman had a little bit of that energy, right?

AN: Yeah, and some hipsters, the Warhol crowd, they had their own little TV Party. That’s a famous early public access television show. From ’78 to ’82. Glenn O’Brien. With guests like Chris Stein of Blondie. Amos Poe. Fab Five Freddy. David Byrne. Debbie Harry. Jean Michel Basquiat. When it really was just a few people putting their tapes on cable access. [laughs]

JTP: To bring it back to mentors, Robert and June, in what other ways would you say that they influenced you?

AN: To me it felt like a family, I guess. Part of me used to feel like they made me part of their family… for whatever reason.

JTP: They were old enough… or maybe not quite old enough? To be your parents.

AN: They were twice my age, yeah. Robert and June are exactly my parents’ ages. June just died at 94. And my dad is 96. I thought of them as my bohemian parents, yeah. And yet they didn’t think of me as their child, for sure. I mean, they considered me part of the family without really talking about it. But they were citizens of the world. Especially Robert. And they knew thousands of people. So I was one of the many people who came into their orbit. And was completely influenced by them. Influenced by them in terms of… even just how they lived their lives. How they put their art first. Above all else. Both of their homes were filled with junk. They never would have—people get money, then they do a renovation on their home and make it beautiful.

JTP: And they never did that. You could just see from the Leaving Home/Coming Home documentary that Robert seemed to have real scorn for the polished surface mentality. There was an authenticity that they held fast to.

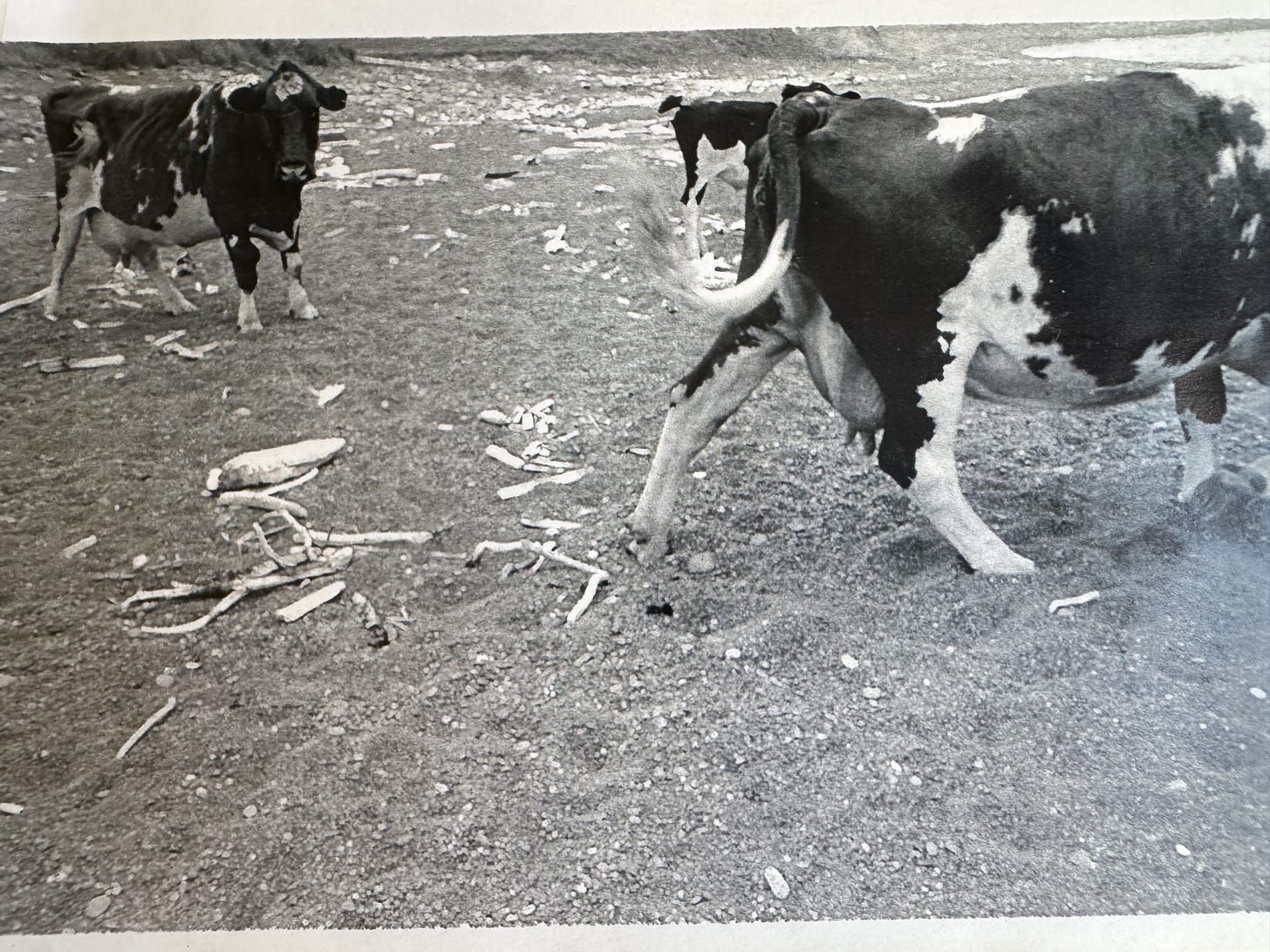

AN: They knew how to live in their community. There were a couple artists up there in Mabou [where Robert and June maintained a getaway home]. Like Richard Serra. And Joan Jonas. But you’re talking an isolated and harsh lifestyle, which artists tend to love. And that place is spectacular. Simple. You know, we’d go to the beach. There’d always be cows on the beach for some reason. I have photographs of the cows on the beach.

JTP: And they’d be there during the winter too, not just the summer?

AN: Yeah, I’ve been up there during the winter. Had Christmas up there, Thanksgiving. We would drive up. When I met them they were going up for Thanksgiving and Christmas, but over the years, I think they stopped going up during the winter. Because it is hard up there. You can see the weather in some of Robert’s films. Like the mailman film where he’s following the guy around on his route. You can see the conditions are brutal. The cliff was windy, insanely windy. And you’d just learn things. We were on the beach and there was a big stump of a log, I remember, that Robert was suddenly like, ‘I have to have that.’ So we built a harness so that we could carry it, and put ropes on it, and we got poles, and we brought it up the hill.

JTP: Four or five of you?

AN: Four of us. I think that time I was traveling with my friend Sara, and she…

JTP: Who had the know-how?

AN: Probably it was June. June was the one with the technical knowledge. They were rugged people. One time I went up there with my partner at the time, Andy, and it was a drought, and they realized that the well near their house had run out of water, so they wanted to open up this spring that was up on a hill. So we dug it out and got a big culvert that was so big. Like it’s really pretty amazing. I’m going to see if I can find this thing because it’s so cool. So we did the culvert. Then when we got back to New York, Robert had photographed me… kind of hard to see… This is the culvert that we went and got, Andy and I. [We looked at a photograph of Annie on a car next to a giant culvert.]

JTP: Oh, hilarious. Whose car was that?

AN: Andy’s. And June made me this, me sitting on the culvert. This is the kind of people they were. The two of them made this for me after that trip. Because the four of us spent ten days doing this thing together. And it was magnificent. Andy’s a builder. So him and June got into the whole dynamics of it and the engineering of it, and the four of us were just covered in mud every day digging it out.

JTP: Most would probably hire out some sort of…

AN: Yeah, yeah, yeah! That’s how they were. Most people would call up a dude who would come by and do it all. But they did everything themselves. Everything.

JTP: Do you think that extremity of DIY—that was just them, through and through. There are probably not a lot of artists who would have that mentality?

AN: June—oh, I was telling you the story about June, Alexander Graham Bell and my ear. Armand, my boyfriend in the 1980s, was an artist, and he made me a copper ear horn. A beautiful device to bring sound from my deaf side to my good ear. When June met Armand, they talked about the ear-horn. So June wanted us to go to the museum because Alexander Graham Bell’s wife was deaf, and he was trying to build her an ear. And June became convinced that she could build me a better ear-horn. We went to the museum, and she was going nuts and studying everything Bell did. And she’s like, “I think I could build you a better ear-horn.”

JTP: Armand’s ear-horn worked?

AN: Yeah, but it was big. And embarrassing. I wouldn’t wear it out. Another story: one time they lifted their Mabou house. Robert made a movie about lifting it. And next thing I know, next time I saw him, he gave me this, which is… ‘June under the house.’

JTP: [looking at the photo] Oh, that’s hilarious. With her arms spread out.

AN: They commemorate life in their work. It means that when you do something together they make something for you.

JTP: That’s sort of the genius of powerful art, right? You’re commemorating a uniquely idiosyncratic moment and preserving it?

AN: Like this is from—I think June did this the very night I met. [We are looking at a drawing of nude woman.] She took me down in the studio and did this portrait of me. And Robert took me into his studio and took me page by page through The Americans and talked about every photo.

JTP: Were you posing nude?

AN: Probably, I don’t know. June drew me a lot. I don’t know what happened to any of that stuff… probably got thrown in the garbage.

JTP: You met her, was it an introduction at a party?

AN: I met her in a Mexican restaurant. [Remarking from her own art collection, as she walks around the apartment.] That’s a June Leaf and that’s a June Leaf. And I have some photos that Robert did. Harder to find. June used to write me these letters. I have hundreds of them but just framed one. When my friend Katrin Cartlidge died she painted that for me. She was always giving me things. We would always bring each other stuff. This is another thing that Robert gave me.

JTP: Very awkward wooden sandals.

AN: And I would get them things. Every time we traveled we always brought home presents for each other. I don’t think I ever walked in [the sandals]. But really it’s about what you learn from people, and being open to changing your life based on what you learn.

JTP: But that’s a radical… I was going to say: you meet this person at a Mexican restaurant by chance, then end up modeling…

AN: That night.

JTP: Just like that. Did you know who she was by that point?

AN: I did not know who either one of them were. My boyfriend at the time, Don, was a literary guy. We went into a Mexican restaurant on 14th St in the West Village and June and Robert sat down at the table next to ours. And he introduced us because he had just met him somewhere. Then the four of us, and I think there was another friend there too, we just talked and talked and talked and talked. And when they went to leave they invited me back to their home. And basically that night they just made it very clear that they wanted me in their life. Then it became just a weekly thing.

JTP: Do you recall how it came to be that you were modeling nude?

AN: She took me down in her studio and said, “I want to draw you.” I can’t remember if I was totally nude. She might have embellished.

JTP: Amazing not to remember…

AN: But I used to be an artist’s model, so it wouldn’t have been a big deal to me to have been naked. And I was young. I wouldn’t be a naked model now, but back then I was a hundred-pound skinny girl. The first ten years I knew Robert and June, we were really, really tight. Like a family. Then I drifted off. I became less attentive. I forget why.

JTP: Changes in your own life?

AN: I think it was when I started going to Haiti to teach film. Then recently after June died, MoMA did a retrospective of Robert’s films.

JTP: Well, you commented on it right when we were walking out from Cocksucker Blues. You said, ‘Maybe Mick Jagger expected more of a glamorizing celebration of their big concert scenes.’ The worship of the Rolling Stones and the crowd. But you really don’t get that. Because it’s more—even the concert sequences—what you have are extreme close ups of him where you can’t even see the crowd. I mean, you can hear the crowd, but you can’t see them.

AN: And the sound wasn’t very good! Danny Seymour was the sound guy who Robert loved. And that was his ‘in’ because Danny was a junkie, so he spoke their language. I think that’s part of the whole trust that developed on the set, it had to do with Keith Richards having a drug connection with Danny Seymour. So they relaxed.

JTP: Then that whole sequence where there’s the woman shooting up in the hotel room. That whole backstage feel, the groupie culture or whatever. Very intimate access.

AN: Because you have an image of yourself. And the image that Mick Jagger probably had of himself was of a handsome sexy talented singer. And these weren’t set pieces to honor their musicality. It was a road movie. A road trip.

JTP: It’s almost a deconstruction of the fame. Like, here are the guys, alone, in these claustrophobic hotel settings. Then, here are the fans longing to have this connection. It’s almost an examination of the phenomenon of fame by really taking it apart. Not showing the big production, the big performance, and letting the audience fall for that spectacle, ‘Oh, look, they’re worshipped as gods!’ But more like, Here are these human beings backstage, nodding off, getting ready in a mirror, doing small things that human beings do.

AN: They had these little handheld cameras. That amazing moment when Bianca Jagger is just watching this little girl’s ballerina. Robert knows where the humanity is and he holds his camera on it. That great moment when he holds the camera on Keith Richards nodding off and holding onto his girlfriend. I don’t remember if I asked Robert, but did he hold [the shot on Keith Richards and his girlfriend] knowing that that ash was going to fall? Because the girl’s forgotten her cigarette and you know the ash is going to fall.

JTP: That moment when Keith Richards is in her lap.

AN: Yeah, and sure enough the ash falls right on his head. And that’s Robert, knowing to hold that shot.

JTP: And if I recall, the shot creeps outwards, then sneaks back in a little. And someone’s sitting a little farther down the bench and looks and sees that they’re being filmed. And there’s a slight confrontation in the person’s eyes, like, Should you be filming this right now?

AN: And a lot of Robert’s photos have someone with a hand up trying to block the camera. And that’s a good shot. It’s like that story Jem Cohen told—he tells this story about getting to the door of Robert’s building on Bleecker Street and Robert opens the door and he has some t-shirt on with some clever phrase, something like Silence is Good. And Jem thought about taking a photo but didn’t. And Robert made some comment like, “Too slow, you should have taken it.” I took pictures of their home, wandering around, but I took very few pictures of Robert and June, because cameras were going off all the time, and I didn’t want to contribute to that annoying click-click-click.

JTP: You did take a few over the years?

AN: Not many. Robert took pictures of me and June. Or they gave me different photos.

JTP: You never turned the camera around on them, so to speak?

AN: No, I never did. On purpose. Robert really liked the photos I had taken in Haiti. He liked my photos. And one day I went to their house and he handed me a camera that was Konica, I think. Some famous photographer had given him one that he used—and he went out and got the same camera for me. Basically saying, ‘This is a good one.’ Which was really sweet.

JTP: And did you end up using it a fair amount?

AN: Oh, yeah, constantly. Because I never do… this [pantomimes taking a picture with an imagined camera held in front of her face and one eye closed]. I always shoot from the hip or from the side. That’s why I loved it when cameras came with those screens you could pop out. You could just hold the camera out and shoot.

JTP: Did Robert do the same thing?

AN: Oh, he did both. And I learned that in shooting in Haiti too. You want to keep the eyeline clear. Because it’s intrusive to put a camera in front of your eyes. So you shoot from the hip. Or down lower.

JTP: Keeping eye contact with the subject. As far as the experience then of going to the restored version of Cocksucker Blues, watching it with Robert, was he telling you of how the production went during the film?

AN: No, on the way there and on the way back. We did a bunch of stuff together. We went on a road trip once to Canada. Just me and Robert. And we’d pull over and photograph stuff. I was kind of his assistant. I would never pull out my own camera when I was with him. At the time he was doing these Polaroids that he would develop in this fixer, developer. He had the two trays in the back of the car. We’d go photograph and I’d do the shaky-shaky thing to develop them. We went way out of our way because he wanted to photograph this mountain of dunnage from a coal factory, this giant, black mountain.

JTP: You’ve been to most of the screenings at MoMA of Robert’s films. Did seeing those reactivate memories of having previously watched any of them while sitting beside Robert?

AN: My main sense is that I always felt like they were family. And I spent a lot of time in Mabou. And on Bleecker Street. And we know a lot of the same people. So, for me, they were all like watching home movies.

JTP: Taking you back—because you could fill out things happening outside the frame that you could remember.

AN: Yeah. Like a Mabou beach shot and I remember we went to see tuna come in, and the Japanese boats were there, and they took these core samples of the tuna, and Robert was photographing that. The Japanese had a bidding war around who would pay for this miraculously high-end tuna. Then, the cows on the beach. And lugging that stump up. So… every time I’d see the Mabou beach I’d have memories of us and the shenanigans there. Or the crows—we’d go every day to see how the crows were doing. Or June taught me how to—I don’t know if you saw any of the movies where she’s in her forge?

JTP: No, unfortunately.

AN: June taught me how to forge in her forge in Mabou. And you can imagine what June made. She was like, “Now see if you can do that!” and she gave me the hot iron. Now here’s what I did [produces a droopy misshapen object and laughs].

JTP: Well, close enough, close enough.

AN: Close enough, yeah [laughing]. That’s the best I could do.

JTP: You said that you drifted a little bit when you went to Haiti. But then… do you feel like you reconnected with June more after Robert passed? Or was it just checking in from time to time?

AN: June and I would have a weekly dinner.

JTP: That seems pretty close. You’re talking recently too?

AN: We always took a walk, she loved taking a walk. She had a Japanese place she loved. And then the last time I saw her she wanted me to just get in bed with her because she was tired. We used to hang out in bed a lot. Watch TV. So, and that last visit, she became curious about what is this AI thing? So I was telling her about Dali and Midjourney and Diffusion. These apps… and she became completely obsessed with wanting to understand it and how do you do it? And I showed her some examples where I was like, “Yes, you can type in ‘a chicken in the style of Van Gogh’ or ‘a chicken in a diner Edward Hopper-style.’” And finally she was like, “Wait! Type my name in.” And I was like, OK. And I wrote ‘a dog in the style of June Leaf.’ And of course ‘June Leaf’: all we got was pictures of June leaves.

JTP: Wow.

AN: And then at some point as she got more and more fascinated by it at some point she shook herself—kind of like how a dog will shake after leaving the ocean—and was like No! No!

JTP: ‘This is terrible!’

AN: Yeah. And then she was like, “But next time you come over I want to look at it again.” And that was the last dinner that we had.

JTP: The whole AI tech-bro mentality is kind of the epitome of everything Robert and June would have hated… Subsume the authentic. The whole, ‘Hey I’m a tech-bro, really all you need to make art is a middle-man as manager to tell AI what to do… That’s all that’s important!’

AN: Right. But they were curious about everything. I remember they were fascinated about Trump. They thought he was hilarious.

JTP: Were they horrified that he won in 2016?

AN: I think they both thought it was hilarious. I think they were very amused by him. Then disgusted by him. But they were amused at first.

JTP: There’s the whole Kill All Normies argument, this book by Angela Nagle, that’s about how through the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s, it was the progressives who had the transgressive culture, the boundary-pushing, Robert Crumb, sex-positivity, maybe a little misogynistic, tearing down of barriers and pushing the boundary on obscenity: that was wrapped into the progressive coalition. And at a certain point, shock, transgression, the right claimed this, bad boy behavior and everything, and the left became more about enforcing norms and toeing the line.

AN: Yeah, that’s possible.

JTP: This is the argument that Nagle makes. With Trump being essentially the shock jock president. It’s an interesting argument. There’s something to it. If you’re trying to get youth excited, having that energy on your side is a positive. Well, we started with mentors. Should we end there? Did that blur for you eventually in New York? A friend could be a mentor could be a friend?

AN: Yeah.

JTP: Do you think that it’s just part of the New York City social ecosystem that things move in waves?

AN: And friendships can have beginnings, middles, and ends—and that’s good. That’s fine. Not everybody becomes a lifelong friend. So you have these flashes of friendship. And you learn from each other.

JTP: From arriving in the ’80s and having these invisible mentors, these people who preceded you in time, but whose generosity of spirit allowed for the life that you lived here, then to mentors you knew and maybe looked up to and were older, and eventually to friends, who in an almost unspoken way, the friend-mentor, where the line kind of blurs…

AN: And I was a teacher myself. I taught always untraditional jobs. I taught in Wassaic, in an asylum for the criminally insane. And I taught for LEAP, an expanded arts program, in the late ’90s. I taught filmmaking boot-camps in the Arctic Circle, for indigenous and aboriginal peoples. Then I taught workshops in Haiti. I taught film in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when I was getting a humanitarian award from Haskell Wexler for the work I’d done in Haiti. I’d fly somewhere and spend a month. And make movies. I’m very good at getting stories out of people. A lot of young people will sit there and say, ‘I don’t have a story.’ And I’ll talk to them for a while until… we find a story. And I’ll say, ‘That’s a story!’ And they’re like, ‘it’s not a big story, it doesn’t matter.’ And I’d say… let’s just work on it. I remember once I was teaching in Tulsa and this one kid was like, ‘I don’t know why I’m in this class; I don’t have any stories.’ And I said, ‘Well, your sneakers are really nice.’ They were white and clean. And he said, ‘Oh, yeah, I love my sneakers.’ Well, why don’t we make a movie about how you feel about your sneakers? And we did, and it was this amazing movie. And he ended up having the sneakers rise like they were elevated into the heavens. So you get the story, then you just put the camera in someone’s hand. And they learn by doing.

JTP: Alright, well, time to elevate to the heavens?

AN: Yeah, let’s go get a drink.