"This Opportunity to Make Something Out of Nothing": Weird Conversations with BEAUTIFUL DAYS Author and Legend of Neglect Zach Williams, Part I

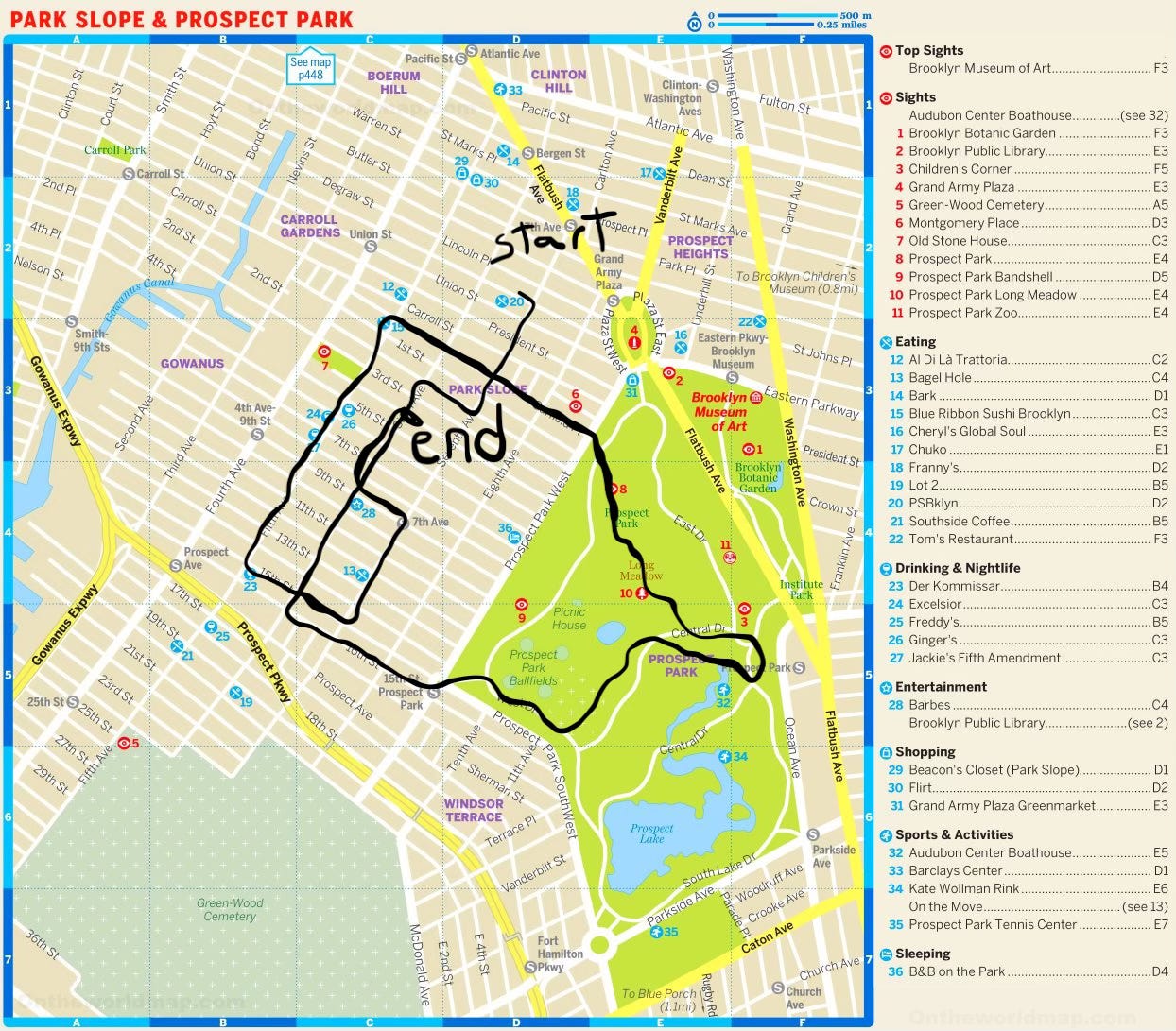

We went for a walk not knowing exactly what route we'd take or who we'd encounter along the way.

I met Zach Williams at the Bread Loaf School of English in, well, if I named a year I would be guessing. Perhaps 2012? He struck me as a bright guy with a winning sense of humor. There was a valence, a vibe, in which I saw some kind of likeness to myself, but it wasn’t a valence I ever sought to define exactly. I didn’t know, for example, until years later when he and I were living a few blocks apart in Park Slope, that Zach had ambitions to write fiction of his own. At the Bread Loaf School of English in Vermont, where most of the graduate students are employed as teachers, I was something of an oddball: a writer and freelance editor and tutor and substitute teacher who placed a premium on the freedom to make my own schedule (following on years of assorted office, or office-adjacent, jobs, in law, book publishing, Hollywood, elsewhere). Insofar as the School of English is essentially “summer camp for book nerds” (I’m not the first to use that phrase), I belonged there, or at least found plenty of pleasure in being there. I didn’t attend to network, nor did I arrive toting the banner of one academic institution or another, as so many of the full-time teachers there did; I just wanted to enjoy a summer reading in the company of other readers. Following on years floundering through New York City writing circles, some published stories, and work for a lit mag, I was after a sense of where the rubber met the road with respect to contemporary literary endeavor (or whatever we want to call it) and what teachers were teaching in their classrooms.

Where I ended up after receiving my degree was the Browning School just off the southeastern corner of Central Park, and I worked as their in-house substitute teacher during the ’15-’16 school year, which, more importantly insofar as this piece is concerned, happened to be Zach’s first leading an English classroom at the same school. We shared several lunches that year—of that much I am certain. The boys there took to calling me “Odysseus,” because of the bushy beard and long hair I was sporting at the time. Within a year, in Odyssean fashion, I’d moved on to the next thing, but Zach remained at Browning for several more, and I’d periodically run into him on 7th Avenue in Park Slope in the early evening. I was usually on my way out, it seemed, as he was on his way home. He attended at least one of my summer afternoon birthday gatherings at the Park Slope Ale House. Then, as happens in Virginia Woolf’s fiction but apparently everywhere else too, time passed, and the last I’d heard was that he’d applied to NYU’s MFA program in fiction; later, I got the sense, without ever inquiring directly, that he and his family had moved away.

Then… “Wood Sorrel House” in the pages of the New Yorker. I was surprised and felt compelled to look up an author photo to confirm it was, in fact, my old cafeteria mate; his own beard disappeared, and his hair grown long, but yes, definitely him. Zach had successfully completed what I suppose I’d call—based on my own experience as a young writer arriving to the city and immediately sending my fiction to both the New Yorker and the Paris Review—the extremely rare Idiot Exacta: hitting up, as an unpublished writer, the two most highly regarded venues for fiction in New York City, a rite of passage that I suppose many young writers must make. Except…? Zach actually accomplished it, publishing his first two stories in those two venerable mags in rapid succession. Which maybe takes it out of the realm of idiocy and into that of, what should we call it?, authorial wherewithal? (I imagine that I can hear him shaking his head and laughing ruefully as I write these words, but then again, that might just be my own particular brand of astral projection.)

In any event, this past July, Zach Williams—passing through town on an East Coast return trip—accepted my invitation to read at the Rogue Loon reading series, which instantiation thereof I hosted on friends’ Upper West Side roof-deck overlooking Central Park. After that event ended, a small group of us, including our host, myself, Zach, and Zach’s friend Anthony made our way to a part of Central Park that was new to me, where we watched fireflies do a little sparkling dance before a modest waterfall under cover of darkness. Then, the next afternoon, as previously agreed upon, Zach and I met in front of Park Slope’s Cafe Regular to start our walking interview.

I could say more about Beautiful Days and my experience of reading it—and hey, I recommend the book, genuinely—but much of my response emerges over the two-part conversation that follows. (Unmentioned over the course of our two-plus-hour walk is the story, “Golf Cart,” which strikes me both as quintessentially Zach and an underrated gem secreted away within the collection, probably my favorite of the batch.)

Zach Williams: Anthony, who we were hanging out with last night, that was his place, right there. I don’t know if you saw me walking from [that direction].

JT Price: Right, I was wondering.

ZW: 140 Berkeley Place. He was there for a few years starting in 2008. We spent a lot of time there. I was working at this little boarding school for severely dyslexic kids up north, in Dutchess County. I would take Metro North down on the weekends, and take the Q train here to 140 Berkeley Place. And everybody that had landed in New York City from college would be there. I have such wonderful, fond memories of that place.

JTP: That was your first Park Slope meet-up point?

ZW: Yeah, yeah, yeah… And whenever I come back, I hang out [with Anthony, in his new place in Gowanus], and it always feels crazy to me how different that ‘Upper 5th Avenue’ stretch has become… They’ve got the nuts store? The nuts and candy store? It’s got a Midtown kind of feel, you know what I mean? But it’s just so pretty here. It’s nice to come back here and walk around. Maybe we’ll live here again someday.

JTP: You guys… moved here when you came back to teach in Midtown. And you were here pretty much the whole time?

ZW: Yeah, when I was teaching on 62nd St., we lived here on 6th Avenue—we lived there for seven years.

JTP: And is that the longest you’ve lived in any one place in your adult life?

ZW: Yeah… yeah. You know the funny thing is this is our fourth year in California, our fifth year coming up. I don’t think we understood that we were going to be there for that long.

JTP: It felt temporary when you moved out there.

ZW: Yeah, and this, here [in Park Slope], did not have that [temporary] feel because we had a lot of friends who lived around here… I was always coming here to hang out with friends, then leaving and going elsewhere. So I really wanted to move here for a long time. Not to diverge, or go off-the-record, but have you been back to Browning at all for any reason?

JTP: Not really. I’ve barely walked by it. And I was going to bring up Browning. I’ve just walked a little bit around the area, that’s about it. Going to the Paris Theater or something like that. Walking along the park there.

ZW: I went to the Paris Theater one time. Working at Browning, over the course of that time, I developed really severe—or I don’t know, what felt like severe for me—insomnia. I hardly ever slept well. Mostly what that meant is I would wake up at 3 or 4, and then, because it takes me so long to fall back asleep, I just knew it wouldn’t happen before 6, when I had to get up. And so the nights when I woke up even earlier, like one-thirty or two, you know. That was like, Aw, fuck. And there were a couple of times, not many, when I didn’t sleep at all.

JTP: All night.

ZW: Awake in bed all night. The only time that’s ever happened to me-

JTP: I’ve experienced that too.

ZW: [nodding] That only time that’s ever happened to me was when I was working there.

JTP: That’s interesting. Because you were teaching for years before that, so you were accustomed to the early wake-up… but something about-

ZW: I don’t know what it was. Maybe it had something to do with getting older.

JTP: And you were a father at that point?

ZW: Good question.

JTP: Because having kids will disrupt sleep cycles, right?

ZW: No, this started before my son was born. After he was born, we slept in the same room with him for three years. So, everything was different after that. But this was before. So one time I left school—I had my planning periods in the middle of the day [at Browning]—and I saw like a matinee movie at the Paris Theater so that I could sleep in the theater before teaching my afternoon classes.

JTP: No memory of what the movie was?

ZW: It was a foreign film about World War I. I slept through the whole thing. But I was aware of it. I think maybe that was the same year I was teaching On the Road. And there’s a passage in that book where he writes about spending the night in a movie theater in Times Square, like a series of westerns—there’s a line about suspecting that in subtle but profound ways every decision he’d made since that night was the result of a kind of hypnotic programming he’d received by sleeping in that theater. You know, hearing the films in his dreams, waking up briefly and then falling back asleep, over and over.

JTP: You were teaching the book, you’d read that passage, and you were like, I will live this, I will do this?

ZW: I think it was after it happened that I read it.

JTP: Gotcha, so when you had the insomnia nights, did you use that time at all?

ZW: No, I never could. Eventually I felt like I needed to try, so I’d get up and read on the couch. But I don’t know. My natural internal rhythms move glacially, I do things slowly. And it takes me a long time to, for example, fall asleep. Or shift any pattern or trajectory like that. So I just didn’t have a sense—it just is not how I’m aware of my body or brain working, that I’m going to go and read a book on the couch and get drowsy and fall asleep. [Instead] I’d just wake myself up more so. So, no…

JTP: I definitely experienced, when substitute teaching—you don’t even know if you’re going in one morning, maybe you get the call, maybe at 5, 5:30 [am], you get habituated to it for three or four days. And then [the job ends]… I’m naturally a night owl. I would find making those dramatic shifts was… I’d often be at Browning, and not have slept, or have barely slept. And I relate it—since I’m talking to you—to reading [short story] “Trial Run,” that sense of We’re here in a workplace, and we’re official people, but we’re all quietly sort of insane.

ZW: Yeah [laughter].

JTP: And this very thin veneer of politeness, or whatever. You capture that very well.

ZW: I wrote that while I was working there, you know.

JTP: The manners behind the manners, like, What is happening?

ZW: I always felt like I had a propensity for getting trapped in weird conversations. I wanted to write about that. “Trial Run” was the first story I started working on in the collection. Although there were other things that I was working on at the time that were more haphazard, and which I never finished. One of them we talked about at Browning one day: I was writing this longish short story—was kind of funny, actually…

JTP: I remember you saying something about the experience of a video game, a Choose-Your-Own Adventure of some kind… When reading “Wood Sorrel House” I found myself thinking about it in those terms. Seem to recall you were going to some conference or something…

ZW: I don’t remember, I wish I could remember that. It sounds interesting. [laughter]

JTP: Well, yeah, as I said, I was often very sleepless.

ZW: The one I was thinking about… I found this book on a stoop here called Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain. I didn’t really read it. I read part of it.

JTP: You put it to your head to see if anything osmotically moved across the blood-brain barrier?

ZW: Yeah, there was kind of a vibe to it, it was a big fat thing from the ’70s with a yellow hardcover and it had the jacket on it.

JTP: An incredible find?

ZW: I don’t think they’re very—you can go on AbeBooks, there are tons of them.

JTP: But something you would not have sought out on your own if it hadn’t just crossed your path…?

ZW: Exactly. It was written by these American psychologists I guess, who… I don’t know how much of this actually happened. But they claimed to have been invited by the Soviet Union in the 1970s to tour various facilities where the Soviets were doing work on ESP, remote viewing, telekinesis… and the premise of the book was, This is a national security emergency. The Soviets are 50 years ahead of us on this research. And they’re learning to weaponize it. And it’s real. And the fact that we don’t even think it’s possible…

JTP: Kind of connects to The Men Who Stare At Goats [2009]?

ZW: It does! It does, in fact. My understanding is that the book was part of the impetus for the ESP and remote viewing program at Stanford Research Institute that began in the ’70s led by these guys Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ. Russell Targ was—oh, this was our old place here.

JTP: Next to the Mexican place?

ZW: The next one… or no, two doors down. Russell Targ was Dan Aykroyd’s inspiration for the character of Egon Spengler in Ghostbusters [1984]. Did you know that Dan Aykroyd wrote that script—that he’s highly steeped in occult literature?

JTP: I did not, but not surprised. Do you want to snap a photo here in front of the building?

ZW: Sure, yeah.

JTP: So, Aykroyd—have you consulted him at all?

ZW: No, but that would be cool. I’d reach out to Dan Aykroyd. Seems like an interesting guy. Anyway, Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ were working on, I think, primarily, remote viewing. They placed an ad, and local people would come in and they would evaluate their abilities…

JTP: That’s the beginning of Ghostbusters, where Bill Murray’s character…

ZW: Exactly, exactly. He’s using the Zener cards, and that’s all a real thing. But this program was funded by the CIA for 20 years. Puthoff and Targ are both still alive and they claim that these effects are real, even though they don’t have hard conclusions about what they are or how to manipulate them, exactly. And they admit that it’s not easy to replicate in a laboratory setting, but that the 20 years of work they did, in aggregate, demonstrates—

JTP: What is the effect that we’re talking about?

ZW: What they refer to as Psi. So, ESP, remote viewing… psychic powers, essentially. So anyway as a result of this book, Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain, I started writing a story set at Stanford Research Institute. But a fictional version, because I’d never been there or anything like that.

JTP: And so that story is not in the collection.

ZW: No, I abandoned it. I did workshop it at NYU.

JTP: How’d that go?

ZW: Fine. But it wasn’t a hard story for me to jettison either. I never felt bad about jettisoning a story.

JTP: Well, yeah, filtering, but are they jettisoned for good, or do you think you might take any of those back up at some point?

ZW: Not that one, no. But there are certain elements of abandoned stories that make their way into newer things. They were just, like, preparatory. You asked me about “Trial Run” and I was talking about that propensity for getting stuck in weird conversations that I didn’t really know how to get out of. And I watched this Errol Morris film, Vernon, Florida [1981]. I haven’t watched it since the one time, ten years ago. He interviews people in this town, and lets them talk for a very long time. So they’re free to ramble. And the conversations, some of them get stranger and stranger and stranger as they go. That was my idea: I want a story that’s like that, only dialogue, and where one character is just responding over and over again, Uh-huh. Yeah. Sure.

JTP: [laughter]

ZW: That was my idea for that story, and it kind of went from there.

JTP: Yeah, and what he says versus what he’s thinking. The radical disjunction between those two things. A psychodrama of sorts.

ZW: Yeah, exactly.

JTP: How much rewriting did you do on that? The original draft versus where it ended up? Through workshops, through…

ZW: I did a lot. A lot of rewriting. On all of them. With the exception of—the only story in the book that I didn’t rewrite or reconsider in any fundamental way-

JTP: [pointing to the bar/restaurant on the corner] That’s a favorite of Bill de Blasio’s, you probably know that.

ZW: Oh, really? I didn’t, but I used to go to the Y here, and he’d always be at the Y. He’d oftentimes be on the stationary bike right in front of me. [laughter]

JTP: Once, was having lunch and he rolled in here with his security detail while he was still mayor. Dylan had just won the Nobel Prize. So I asked him how his wife at the time, who I understood to be a Dylan fan, felt about it. And he said, you know, it was cool. I was talking to him, standing from the table, and my friend who I was having lunch with snapped a picture of me standing alongside him. I was in full Lebowski mode: knit cap, long beard, sunglasses, ridiculous. Anyway… memories.

ZW: Have you read that story that’s in the New Yorker about an upstate college professor’s reaction to Dylan winning the Nobel Prize?

JTP: No [laughing]. I should track that down.

ZW: It’s so good. It came out shortly after he had won the prize. By Joseph O’Neill.

JTP: Right, Netherlands. It’s this version of Gatsby that revolves around international cricket players in Brooklyn.

ZW: The story is the only thing I’ve read by him, but I need to read more. That story is really great. The only story I never rewrote really, substantially, was “Red Light.” That was one where—you asked me about using insomnia time? I’ve had three stories— well, one of them was just the other night before I came up here; I don’t know what will happen with it, but—three stories that appeared more or less all at once during a sleepless night. I can’t sleep, and I’m lying in bed, and then something is just palpably there all of a sudden. It’s just a rush. That’s just the absolute greatest—those are the things that keep you going.

JTP: You have a vision! A gnostic experience?

ZW: Yeah [laugh], I suppose you could call it that.

JTP: Time isn’t real, and you’re going to pull back the veil?

ZW: [laughter] Yeah, something like that. The two cases in the collection were “Red Light” and the story “Neighbors,” I couldn’t sleep, I had insomnia, and then, the story was just right there. And I had to get up and write it. In both cases, I got up at five in the morning after not really sleeping and having these kind of weird, liminal visions, and banged out full drafts. I work really slowly—so this is highly, highly unusual.

JTP: One sitting?

ZW: Yes. In “Red Light” there really was very, very little that changed.

JTP: Did you workshop that story?

ZW: No, I never did.

JTP: Cuz I was curious [laughing] how a workshop would react to it. It’s delightfully deranged.

ZW: I thought about reading it yesterday. I’ve never read it. A couple of times I’ve thought about reading it, then I’m like, Um, maybe not. Where are we? (I mean, I know where we are.) But do you think we should turn up into the park?

JTP: Sure. My idea… maybe we ramble, then come back and wrap it up in front of the building where you used to live? A circle of sorts.

ZW: Yeah! In “Red Light” very little changed, but there were tonal tweaks. But still, I worked on it for—there’s nothing in the collection that I didn’t work on for years. Including “Red Light.” Over and over again I would open the document and tweak it.

JTP: When did you start writing fiction of your own? Before workshops at Bread Loaf, or…?

ZW: Yeah, and well, I never took workshops at Bread Loaf. Because I always—I wrote for pleasure as a kid. But not in some sort of…

JTP: I saw your Masters Review interview where you allude to alien abduction or alien visitation-type stories…

ZW: I did. I liked getting writing assignments in school. [A strong wind comes on] When I was older, like, in high school, we would get a few creative assignments per year, and by senior year I remember really relishing those. I wrote some things I felt proud of afterwards. I remember thinking it was fun to get the assignment, because I knew it meant that something would happen, but I didn’t yet know what it was… This opportunity to make something out of nothing.

JTP: An opportunity to surprise yourself.

ZW: Exactly. The deadline aspect of it made me certain that it would happen at some point, you know?

JTP: And I’ve heard you, if you want to embark on this half-tangent, but not really, in regard to what you just said, I’ve heard you describe the process for this musical—I don’t know whether to call it a band or a project…?

ZW: Legends of Neglect.

JTP: It sounds somewhat analogous in ways? Making the music all at once as opposed to having the production be over a long period of time.

ZW: I’ll just quickly before that—I majored in Creative Writing in college. I was at Johns Hopkins, so I took classes with Stephen Dixon.

JTP: A legend. Writer’s writer. Quintessentially so.

ZW: He was the first writer that I ever saw in person. I would sit in his workshop absolutely fascinated and enthralled by him. And I was reading his fiction—it was the first time I had the experience of connecting the person, and his personality, to the work on the page. And I loved his work. So that was hugely influential. And I wrote a lot in college. I don’t think there was much in the way of craft instruction. Not that there was none… Well, probably the problem was more me than anything else. But I never revised anything. I didn’t understand that I wasn’t revising anything. I just didn’t really know…

JTP: You’d receive an assignment, you’d fulfill the assignment, then move on.

ZW: Yeah, exactly. Then when I got out of school, I had very little success writing short stories on my own.

JTP: In the sense of not feeling inspired to do so? Or in the sense of trying and being like, This isn’t working?

ZW: Like, This is bad. And yeah.

JTP: Do you think that that was true? Or just a feeling you had [at the time]? Were you showing these to people and getting responses?

ZW: No, I think it was true. I don’t know what it was… But I wasn’t showing them to anyone, and maybe that was it. In the undergraduate writing seminars program, there was a really lovely community. Really good writers. It was the people in the year below me who were sort of more movers-and-shakers. And they started an undergraduate reading series, which there hadn’t been previously. So we had these big, well-attended, fun readings.

JTP: Did any folks emerge from that as published authors that you know of?

ZW: There’s a guy named James Zwernemann who I just saw is publishing his first novel this year. And a guy named William Camponovo who’s a great poet. Another guy wound up writing for the Wall Street Journal.

JTP: Writing that pays. No problem with that.

ZW: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Being that John Hopkins is a research institution, we had this little kind of enclave, the writers. And it was great. So maybe it was the loss of that, the sense that writing was a thing happening in the context of these particular people—and after I graduated I had a really lonely year. I moved to LA. First year after college I moved to LA just kind of on a whim. Did I ever tell you about this?

JTP: No, this is good.

ZW: This is all good stuff.

JTP: [doing a voice] Content for the mill, baby!

ZW: [laughter] I had an internship at Beacon Pictures.

JTP: I also did a year in LA. Or, well, half of one.

ZW: Did you?

JTP: For Valhalla Pictures.

ZW: Oh, man! I didn’t know that. I wonder if we talked about this like ten years ago?

JTP: No, no, I don’t think so.

ZW: I have a bad memory, so. I had this internship, I got fired from the internship: there was a guy who was the intern coordinator… Rich was his name. I wonder where he is now. He was 28 or something, which seemed old to me. And he brought on a number of interns, a number that was then judged to be too high. There were all these kids walking around the offices. The more senior people started to get pissed about it. Then one day, the interns all—there was a cocktail party at the office, in the evening. And the interns all stayed and went to the cocktail party, but weren’t really supposed to. So then they were like, You have to fire all these interns.

JTP: For going to a party uninvited, my god.

ZW: So after that I got a really good job: I worked as an assistant to the post-production coordinator on this movie called El Cantante [2006], which is Jennifer Lopez and Marc Antony. It’s a biopic of the salsa singer Hector Lavoe who was not somebody I knew about before working on the film.

JTP: I was there in 2003, so not far off. Working on Ang Lee’s Hulk [2003]. I was just a gofer, running around. It was a huge bomb. He brought this majestic, contemplative approach to comic book material. And they also used a screen technique where they made comic book panels on the screen. Which, you know, interesting idea, but in the offing it was sort of awkward.

ZW: I hate superhero movies, but I want to take my son to see Superman [2025].1 It looks fun.

JTP: Of that movie type, I think James Gunn—he did Guardians of the Galaxy [2014]—is one of the best doing it.

ZW: I did go see Guardians of the Galaxy, I went to see it here, by myself one day. I used to go to a lot of movies by myself after work or whatever. Whatever year that was—I was a different, more innocent person back then. Because now essentially I don’t want anything to do with anything that’s in the popular sphere. [laughs] I want to be as far away from it as I possibly can be.

JTP: Describe that feeling: Is that to preserve a creative integrity of your own, and not be polluted by whatever’s in the mainstream?

ZW: I don’t think it’s about my own creativity. I think it’s a sense of being surrounded and inundated to a point of poisoning by just… shit, everywhere, constantly. Everything I’m scrolling past on my phone. That’s the main culprit.

JTP: You hear references now to ‘AI slop’ or whatever. But even like Netflix content, which somebody is actually paying to make, is-

ZW: Slop is a great word. But also part of it for me is because I’m fairly weak-willed and lazy. And I don’t do a great job of guarding my own time. I have a pretty compulsive relationship with my phone, and-

JTP: These are the great David Foster Wallace themes…

ZW: Exactly, exactly. A lot of it is anger at myself out of a sense that if I don’t get a little pissed off about this then I’ll never right the ship. [Anyway] I’ll just say quickly that I worked on this Jennifer Lopez film. And it was a really good job because it was outside the studio system? And that was the only reason I got hired—a studio wouldn’t have hired me, I didn’t have any experience—

[A municipal garbage truck pulls out onto the inner circle of the park where we are walking, loud and beeping]

JTP: Let’s cross over.

ZW: [referring to the truck] That’s aggressive, man.

JTP: [joking] Look out, it’s the government. They’re on to us. Trying to shut us down!

ZW: I had the classic experience that maybe you had too of working 24/7. My boss would call my cellphone at 7 o’clock on Saturday morning with a question, then again with another question. Then, at 7:30, she’d call again and be like, Alright, get up, get your coffee, let’s rendezvous at the office at 9. And I’d be like, Ah, fuck. I did that for several months, and after that, I got hired thru a temp agency to be the fifth assistant to Jerry Bruckheimer.

JTP: [laughter]

ZW: And I worked in Jerry Bruckheimer’s office for several months. I got fired from there eventually. It was a temp-to-hire position. Apparently, I stuck around longer than most.

JTP: Oh, so they were really churning through people?

ZW: They were churning through people, but I did—I want to avoid sounding self-congratulatory or something— but I got fired for reading at my desk. Because Bruckheimer would go—they were doing Pirates of the Caribbean 3 [2007] in London on that big soundstage. And my job was to run his errands for him when he was around. Like, he’s famous for his fountain pen collection. He has a massive collection. I’d always have to go to the Mont Blanc store on Rodeo Drive.

JTP: [laughter] He was always adding to it? Or special orders?

ZW: Everybody would give him pens. Everybody knew that he loved these pens. So he received them frequently as gifts. But the pen collection was worth an incredible amount of money. As I recall, he had jewel-encrusted pens. He had another that was gold that had a bust of Shakespeare at the top. There were all in a big display case in his office that I was not allowed to go into.

JTP: The office or the case? Or both?

ZW: The office. I mean, once or twice I did. But I wasn’t supposed to go in there. So when he was gone, filming, which he’d be for weeks at a time, there was nothing for me to do. And I did a bad job of making myself look busy. I would sit at my desk and read books. And somebody warned me that I shouldn’t do that. That it looked bad. But I still did it. And they fired me.

JTP: Good choice. Good choice by you.

ZW: And I wrote fiction. At the desktop computer there. When I got fired from that job I decided to apply for English teaching jobs back East. I always thought I wanted to be a teacher anyway. Then I got busy with being a teacher, and for years I didn’t do any writing. That was kind of a dark…

JTP: And you felt that? A creative frustration? A desire, like, I still want to write but I’m overloaded with… whatever. Structuring things and running the school year. And enjoying the summers. And Bread Loaf.

ZW: Exactly. I just got totally waylaid. Teaching was hard. I had to learn a lot about how to do it. It took me years to learn how to do it. And I don’t know—I was young, too.

JTP: You taught in high school for ten years?

ZW: Twelve years. The last one I was concurrently in the NYU MFA program. And our son had just been born the year before that.

JTP: I remember I would run into you on 7th Avenue… and yeah, you were parenting, you were busy in all sorts of ways, and you’d have this sort of rueful tone, like, Well, back to the salt mines… in regard to teaching.

ZW: I started to feel… When I got into… What I said earlier, about how when I wrote in college, I didn’t even really understand that I wasn’t revising my work? It wasn’t until my 30s that I realized how hard it is to actually finish something. To bring it to a state of completion. That goofy psychic spy story that I referred to, I think that that was the first thing where it just sort of clicked, like, Oh, if I actually want to finish this, if I actually want this to be good, that’s kind of a whole different… I saw how much I needed to learn in order to be able to finish something. And that’s when I started to feel that time was a problem.

JTP: Did you teach some of that to yourself by taking on revisions? Or was that the MFA program? Or some combination of both?

ZW: Maybe it was a combination of both? But I really think it was the MFA program, though. ’Cause I know that I went into the MFA program thinking… I wasn’t sure what to do… Part of what I was going to say earlier is that I didn’t take workshop classes at Bread Loaf because I had done that all through undergrad, and so I wanted to take English classes.

JTP: Ha, same. Filling in the reading gaps.

ZW: Is that how you wound up at Bread Loaf?

JTP: Specifically I wound up there because I already had an MFA in fiction but I was tutoring and substitute teaching, and so my income dramatically dropped during the summer. And with the campus job [at Bread Loaf], and the funding, I could sublet my apartment… so I ended making a few hundred dollars during the summer instead of scrambling around being like, What am I going to do? So that was the impetus. But yeah, also, it was just purely enjoyable for me.

ZW: It was great, wasn’t it?

JTP: I loved it.

ZW: Did you have a standout class?

JTP: Michael Wood, clearly amazing.

ZW: Which one was that?

JTP: I took two classes with him: one was “Modern Poetry.” And the other was “Theory and Criticism.” And he was just incredible. As a teacher. Such a gifted conversationalist, and just very gently steering things. And also keeping it at a very high level. And there were other great courses. I mean, Jonathan Freedman…

ZW: I never took a course with him.

JTP: His health obviously suffered, eventually. Very young for that, and a tough situation. But one of my summers was taking one class with him and one with Sara Blair [his partner].

ZW: I never took her either.

JTP: And I loved the syllabus of his course. It was mainly film-based, called “Jews and Film.” And yeah, at the time, I was frustrated a bit because as far as the teaching it felt like he was phoning it in a bit, like, This is summer camp for you guys. And I was like, Be more rigorous! Now I feel bad about that, in retrospect. I guess he had the right idea to live it up in the moment. But those were both great classes—Sara Blair’s, too, which was on new media. We read, for example, Henry James’ In the Cage, a novella revolving around the advent of that cutting-edge tech, the telegraph. How about yourself?

ZW: My first summer I took “Thinking Theory” with Michael Wood. And he had us read Benjamin and Derrida and Adorno and Freud. And I had absolutely no exposure to anything like that. And everybody in the class was very sharp. I felt extremely out of my league. I remember feeling, Maybe I can’t really do this, or maybe I’m in the wrong place or something. I had a sense of, This is a different sort of academic experience than I’ve had before. And I retained very little of any of the individual readings…

JTP: That’s often the nature of survey courses, right, where you’re just sort of flying through things? But being exposed to them [is what matters] and seeing what lights up.

ZW: There was a Benjamin essay that I always remembered. It has one of my favorite descriptions of a nightmare. He had a nightmare as a kid about walking to the top of a staircase that was haunted by this invisible presence. And he walks up and up, and at the top of the staircase, on the final steps, this presence holds him spellbound. That’s what he wrote: on these last stairs it held me spellbound. That’s what a nightmare feels like to me too. And that’s something that I’ve aped or quoted a couple of different times in different stories. That line stuck with me. I understood very little of what I was reading, but it was very energizing for me to be in the room with Michael Wood talking about those texts. And that same summer I signed up for a Shakespeare course taught by Susanne Wofford. I can’t remember what happened, but for some reason she couldn’t do it. So her husband, Jacques Lezra, taught it. And he was amazing.

JTP: An NYU prof.

ZW: I guess so, right? That course was called “Shakespeare and the Mediterranean.” It was Merchant of Venice and The Winter’s Tale and things like that, in the context of the 16th century Mediterranean trade economy. We read Turkish pirate captivity narratives. That was a great class. And if there was one that was the one, though? I did a summer in Oxford and Jeri Johnson’s “The Modernist Novel” was… totally mind-blowing. And it was one of the scariest academic experiences that I’ve ever had. It was very demanding. There were five of us in the room. And she would cold-call people?

JTP: So rare these days, it seems.

ZW: She called on me to define “pastoral romance” or something like that. And whatever I said didn’t cut it. She’d let you know when that was the case. We read a novel a week, and in order to be prepared for the three-hour meeting you really had to have written your own paper on the book ahead of time. Early 20th century and late 19th. We read Tess of the d’Urbervilles, we read The Good Soldier. It was building up to, the end of the course was A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and To the Lighthouse.

JTP: That was a good class too: Jenny Green-Lewis teaching Virginia Woolf.

ZW: We were in that one together. But the [Johnson] class was so demanding, I worked so hard for that class… it makes me feel guilty that I can’t be that kind of teacher? I don’t have the right personality for it.

JTP: It’s also very much against the grain of, I want to say, fashion… but just practices these days. What’s acceptable or considered acceptable.

ZW: Absolutely. And she scared the shit out of me. In the best way. She was stern and demanding. But when you did a good job she let you know.

JTP: And you feel there’s some—a term like ‘use value’ is kind of gross, but you feel like you got something from that?

ZW: Yes. I loved that class. I think it changed my life, really. Every time I’ve had an experience with a teacher like that, who won’t bullshit you…

[We turn into view of a boathouse in the northern section of Prospect Park where there appears to be a wedding in progress.]

JTP: Apparently when Scorsese adapted The Age of Innocence [1993], I think they used this boathouse in one of the scenes. The film with Daniel Day-Lewis and Winona Ryder.

ZW: Yeah, I used to show that film to my students. I love that book.

JTP: Yeah, it’s great, great, love it too. And the adaptation, it’s good enough.

ZW: We used to walk with our son here all the time. After we had our son, we spent way more time in the park. Just to get out of the apartment.

JTP: Sort of the backyard to the entire borough, right?

ZW: Exactly. Before we had him, we might wake up on a Saturday and lounge around with coffee.

JTP: We’re seeing a wedding here. A middle-aged wedding? A second wedding? Just to speculate about what we’re seeing. I’m going to take a picture. [the wedding breaks into cheers. A Brooklyn writer familiar to me walks by from the opposite direction—a writer who, for one reason or another, has asked to remain nameless here.] Hey, how you doing?

BW: What’s happening?

JTP: Conducting a writer interview here with Zach Williams. Zach, [Brooklyn writer]. [Brooklyn writer], Zach Williams.

[Exchange of pleasantries.]

BW: How’s the interview going?

ZW: I think it’s going great. [to JTP] What do you think?

JTP: Ah… pretty good, pretty good. You’ll be in it now. Do you want to add anything? We were just talking about how this boathouse was used in The Age of Innocence, Scorsese’s adaptation of that important novel.

BW: [looking at the wedding ceremony and the harpist playing there] The harp is nice.

JTP: Well, it’s sort of gossip, but thought maybe it would be fun to share... [repeats a story that happened at a recent reading series where a writer went on and on and on way past the allotted time.]

BW: I was there. I’ve been to a reading or two in my life… but that was wild.

[BW and JTP discuss what happened in more detail.]

JTP: Trying to give Zach ideas for his next reading. Do something really memorable?

ZW: Yeah, right, right, right.

JTP: I went to a reading two nights ago. It was for the novelist Lee Cole. Fulfillment. He read for thirty-five minutes. But I thought… I dug it. Good excerpt. He definitely hadn’t lost the room.

BW: Dangerous game, though. Maybe the most dangerous game.

JTP: Hunting humans, yes. But above that?

BW: Reading a little bit too long? That… well, I’ll let y’all continue. Nice to meet you.

ZW: Thank you. [BW exits stage right.] What were we talking about? Bread Loaf. Probably OK that we get off of that.

JTP: One thing to add is Stephen Donadio. Stephen Donadio’s courses were some of the best.

ZW: Oh, yeah! I took him in North Carolina. I took Faulkner with him. I know that for some of my friends his approach didn’t work—it seemed like he’d been teaching that class the same way for years. It was the only English class I’ve ever had where all the questions were posed with like a really hyper-specific answer in mind? You’d raise your hand to answer a question, and he’d be like no. No. And the correct answer was “Luster’s quarter,” or whatever. But he was teaching us how to read meticulously. He taught us how to read Faulkner. I always liked the professors who are a little quirky. Anthony and I took a comparative government class in undergraduate that was taught by this guy Gottfried Dietze who was 82 when we took the course? And he would just get way off topic and tell these rambling stories. Then he’d give these exams that were typewritten exams? That he’d clearly had in his desk forever. And the exams sometimes connected to what he’d talked about? But often didn’t. His stories, though, were so good. We loved the class. It didn’t make any sense. We got Bs—I think everyone did. Some people really didn’t like that because it screwed them up. But it felt kind of worth it because—like, he told this story about going to Tiffany’s by himself as a young man, to look at the wedding rings, after this romance he’d been in had collapsed. So he would go look at the wedding rings by himself.

JTP: Hey, that’s literary material.

ZW: And so he talked about being in there one time and bumping into Picasso’s daughter, Paola Picasso? He said, ‘I approached this young woman and said, Pardon me, but I believe I know your father. Are you Paola Picasso? I can tell from your eyes.’ He would tell these stories like that. And then he died. He died the next year.

JTP: The precarity of life and experience: that’s in your fiction too. The unlikeliness of given moments, you capture that well. In a story like, say, “Lucca Castle.”

ZW: Yeah… that sparks a thought in me that I don’t quite have at my fingertips, but I’ll keep thinking about it.

JTP: Well, in that story, the question seems to be, Is this just a coincidence or meaning that’s guiding me to something? And the randomness and piling up, these occurrences building toward some absurdist culmination that also says something about where the culture is at and such. Have you ever read Lethem’s Chronic City?

ZW: Yeah, loved that book!

JTP: Because I was going to say that “Lucca Castle” definitely felt in that spirit.

ZW: I’ve been meaning to re-read it. You know how I read it? They had a copy in the Browning library. Which is kind of funny, right? I haven’t read tons of Lethem, but I really loved that one. What year did that novel come out?

JTP: 2006, -7, something like that?

ZW: See that feels pretty—I know he’s a huge Philip K. Dick guy.

JTP: One hundred percent, yeah.

ZW: But the way that that novel dealt with those sort of gnostic reality themes in terms of the internet and the question of sitting around on the computer and not being quite sure what’s true outside the four walls?

JTP: The chaldron.

ZW: Exactly. And the Marlon Brando thing. That strikes me as pretty prescient for the time. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I didn’t read Philip K. Dick until later… As a kid I was always interested—not in an academic or intellectual way, but in a sort of more intuitive way or something?—in questions about the nature of reality. I think I’ve always had something like mild dissociative tendencies. Barbara Ehrenreich has a book, Living with a Wild God. She writes about having what she terms mystical experiences that were very powerful… and shaped the outcome of her life, she says. In the book, she uses her journal from when she was a kid to re-interrogate those experiences. When she was thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, she wrote in this journal that she viewed herself as on a mission to figure out what this is. Because it, life, did not intuitively make sense to her. I was reading Virginia Woolf’s diaries recently? And she has—she writes about similar things in a couple of different places. Although I’m not, you know, a comprehensive reader of this stuff. But in two places that I counted, once in her diary and once in “Moments of Being”—she writes about an extraordinarily profound moment in her life… when she stepped over a puddle. And looked down. And saw the puddle. And saw her foot. And just for one second didn’t know what anything was. A moment of full dissociation. My sort of puddle moment was—I had this one semester in college when I was really depressed and anxious. And I was sitting in a seminar with Stephen Dixon. And I had the exact same kind of moment—I looked up from the desk and didn’t know what anything was. Like, anything. What separated things. Or how to understand what the separation was between the people and the furniture and stuff like that. It was for probably far less than a second. But it had a big impact on me. And I’ve since had any number of experiences like that. I think as a writer you cultivate them. Now I find it interesting, but as a kid, in college, it was scary. I was always—when someone on campus would get a bunch of acid, well, I never touched that stuff because I was always…

JTP: Even as a devoted Phish guy with all the stereotypes that would bring to mind?

ZW: I always struck people as a kind of druggy person. But I’m not. And I always had a sense that it would be a little dangerous for me to take hallucinogens. So I never did it. In terms of the “Lucca Castle” stuff and unreality or coincidences, or questions about the way things connect? I think that’s always been a sticking point for me. Ben Okri said something like, “My short stories are always investigations into the nature of reality, which must be the most contested thing in existence.”

JTP: You’re talking about influences like Virginia Woolf’s diaries, or Barbara Ehrenreich reflecting on her own lived experience, and what people might consider less credible extraterrestrial phenomena and these sort of edge cases of professed consciousness, like Whitley Strieber, that kind of thing. And what links them: What is reality, and how do we make sense of these things?

ZW: Yeah. I was always fascinated with that sort of question. And yeah, occult subjects that might seem silly or less credible, as you say, like UFOs, do have a way of pointing toward these larger, more perennial concerns. There’s a guy, John Keel, who was a sort of interesting fringe personality, a fairly eccentric character—he wrote the book The Mothman Prophecies?

JTP: Oh, right. Cited in High Weirdness by Erik Davis.

ZW: Yeah. Keel’s a strange guy, and reading him is weird. He wrote about UFOs in the ’60s as a self-styled investigator. And he said that the thing about UFOs, as a topic, is that you start off thinking prosaically about it—Oh, someone saw something in the sky, what could it be? Looked like a ship? It was metallic? Let’s try and figure it out… You start with that, but it’s slippery, and before you know it you’re into the nature of perception, and the nature of reality, and Hermes Trismegistus and Hermetic alchemy and gnosticism and that kind of thing. It’s this question about the nature of anomalous experience—momentary punctures in the fabric of reality? Why do people see weird things in the sky? There’s this broader human context…

JTP: As a subject treated in your published stories, or maybe in relation to what you’re working on now, interested in now—well, even the final story in the collection, right? “Return to Crashaw” has… almost the absurdity of trying to put this sort of stuff in an academic context… and the tide going out on interest in this site of knowledge [a historical site in the story], and it’s all been arranged as a museum to be made comprehensible for a tourist audience. Just to build that around this mystery, a culture around that… yeah.

ZW: One big influence on that one in particular was Solaris by Stanislaw Lem? I haven’t read that in a long time, but I thought it was so funny—and so distinct from the film. But the novel as a critique, or parody, of academic culture, right? Generations of “Solaricists” working on this problem of figuring out whether the ocean on this planet might be conscious, and whether they might be able to communicate with it… Definitely a lot of that went straight into that story. That was a fun one to write. It almost didn’t make it into the collection because… I started that one fairly early. Then I just couldn’t get the language right, or what felt right to me? I set it aside for a really long time. It sat for a few years. I came back to it and figured out this second-person mode of address that really felt good. Then I was able to finish it. That was a hard one.

JTP: It does speak to the direct experience of teaching in ways.

ZW: Yes! Yes. In my initial—it’s funny you say that. For each of my stories I have a notes documents that sits next to the drafts in my files. And the notes documents are a kind of a running dialogue/conversation with myself. And in many cases the notes document is far, far longer than the story. Maybe 70 pages longer…

JTP: It’s a resource, a place to mine what will become the story.

ZW: Yeah, so “Return to Crashaw,” the very first inkling of it, the first thing I put in the notes document, was this recurring dream I had about teaching a class that gets progressively more out of control until there’s not even a center to anything anymore. It’s like your throat is hoarse and people are laughing and…

JTP: It’s sort of built into the story, isn’t it?, the almost Plato’s Cave allegory where they have the staged version of the monuments versus some of the characters’ desire to go right to “the real thing”… but of course the caretaker is there notionally to keep people away from that? For reasons of sanity, or whatever?

ZW: Right, right, and that makes me think of that one Ben Okri story in the New Yorker—did you read that one?—about the search for “real” water in a world where all water is synthetic. About young people searching for real water.

JTP: So when did you—you said you were teaching for one year at NYU—what precipitated being like, OK, I’m going to pull up stakes from the teaching game? This high school where you had a job for some number of years and could have kept going in theory… What was the moment where you were like, I’m going to try and take a real run at this and see what happens?

ZW: I—and I apologize because I keep catching myself going back to threads from earlier-

JTP: All good, do it! We’ll fix it ‘in post.’

ZW: Edited and condensed for clarity. Before we started talking about Bread Loaf I was on the track for that… working on the psychic spy story and a couple of other things. And I sent them to a friend of mine, a guy named Douglas Watson. He’s a brilliant writer. And he’s in Legends of Neglect, the first couple of records.

JTP: Speaking of going back to prior threads, do you want to take a moment and explain what Legends of Neglect is?

ZW: Oh, sure. Because when you asked me to do a walking interview, I liked that concept because all these threads feel very linked to—so this is when we were over on 15th Street and you asked me if I was showing my writing to people after college or not, and I said I wasn’t really in a community then and I didn’t know how to do it on my own… Then I became a teacher, and it was a year or two after that, I was here, in New York, at Anthony’s old place on Berkeley, and this guy Dave who had gone to school with us, who Anthony knew better than I did, called up Anthony. And he said, I’ve got a four-track at my place, do you guys want to come by and we’ll make a nonsense record today? I think that’s how he termed it. So we went, along with my friend Richie, my closest friend from Delaware growing up, going back to elementary school, who also was at Anthony’s place that weekend. We were very hungover. Let’s see this is 3rd… Do you want to—?

JTP: I was thinking we could walk back to the building where you lived and wrap it there?

ZW: I’m happy to keep talking too. I’m not in a hurry.

JTP: OK, we’ll see, let’s not force it either.

ZW: So Richie didn’t know this guy Dave. And I didn’t know Dave that well either. But for some reason we agreed to do it. We went to Dave’s old place. And Dave is such a brilliant creative person. He’s got this kind of frenetic energy. He’d always been in bands. And been creative in a way that I wasn’t, really. What they did for fun, he and his friends, growing up, was they made short films, they made music, they were in bands—it was all they ever did.

JTP: Inspiring each other to participate in this kind of thing.

ZW: Yes [birds chirping loudly], and they had this punk ethos of ‘first thought, best thought.’ No revisions. So we got over to Dave’s place and there were a bunch of people there. Eight or ten maybe. And Dave was like, OK, let’s do it, let’s get started. My concept for the first song is ‘Blast Off for Kicksville.’ It’s this old movie reference, “Blast Off for Kicksville.” He was like OK, I’m going to play the sample from the movie, and then everybody start shouting, ‘Blast Off!’ And we’re gonna do it like this—

JTP: [laughing]

ZW: You got to bear in mind this was like 2009 or something. We were in our twenties. So… he had an electric bass and some pots and pans and a banjo. And he had an omnichord, and stuff like that.

JTP: People were playing instruments that they knew, and some that they didn’t know?

ZW: People were not musicians. I played the drums, but at that point I don’t think I knew how to play guitar. Or maybe I did, I don’t remember. I was hungover. And I was really, really miserable. And it felt like this was the weirdest, most awkward, embarrassing thing.

JTP: Forced.

ZW: Forced! I was like, I don’t want to do this, this is so weird. And lame.

JTP: You felt that in the moment of having arrived? You got there, willing to do it, then you were like, Oh god.

ZW: Yeah… yeah. Yes. Richie and I were probably looking at each other like, Let’s get out of here. Then…

JTP: You were ready to neglect the Legends of Neglect?

ZW: Ha, exactly. So we did it. We did this first song. And then Dave was like, Who’s next? Who has the next song? And somehow suddenly it was like we all had ideas for songs. He sort of just made us do it.

JTP: So it sparked. Did you go very quickly from being like I want to get out of here to OK!

ZW: Yeah, it was like a switch flipping. And I don’t know if this will sound corny or look corny in print, but it was like a kind of—hey, look at that [we see crossing the street toward us, Jerry, Diane Mehta’s partner, a poet who read the night before with Zach at the Rogue Loon reading series].

JTP: Hey, Jerry! We’re doing an interview. You’re in the interview. Do you have anything to say for the interview?

J: Hey! Good to see you! Great reading! And good to see you!

ZW: That’s funny.

JTP: Maybe we’ll run into the ghost of Paul Auster next. All these coincidences.

ZW: Did you ever bump into him in the neighborhood?

JTP: I did. And I interviewed him. At his house, yeah, for 4 3 2 1. The conversation was very much about mortality.

ZW: Aw, man. Jeez. Glad you did that.

JTP: One cool moment [of having run into or seen Paul in the neighborhood]: being in the middle of the pandemic, and I know he and Siri would spend significant parts of the year in Europe and all that… and I remember being like, it was the pandemic and seemingly half the population of Park Slope had gone to their vacation homes or otherwise moved out and I remember thinking, Yeah, well, they’re probably—because I would see him regularly walking up and down 7th Avenue—so I was like, they’re probably in Europe or something, or at least they’ve probably gone somewhere to get away from all this. And then… maybe in month two or three, looking out the window—I was working on a novel and really kind of cloistered and shut-in—and looking out and seeing Auster in all black walking down the street in front of Key Foods. And being like, Ah! He’s here. He abides.

ZW: Did it give you some resolve?

JTP: Yeah, totally.

ZW: That’s cool. I felt that way one time. It was a Friday, I think. I had kind of a bad week teaching and I was walking around—sometimes on Fridays after school I’d walk from 62nd St all the way down to East Broadway and take the F. And I saw… I saw Deerhoof. I don’t know if I saw all of the band—I saw Greg and Satomi. And they were walking into a restaurant, getting dinner. I felt—that gave me strength. That’s Deerhoof, man. I want to be like them.

JTP: Ha, so, you were describing the Legends of Neglect experience?

ZW: We wound up working on this recording late into the night and I think we came back the next day. It really sparked, it was so fun.

JTP: And it’s all out there?

ZW: Yeah, it’s all there. I’m not necessarily suggesting that anybody go listen to it.

JTP: [laughter]

ZW: Although we wound up making three records over six or seven years, in this same configuration—we kept coming back. And we got better at it over time. I think we’ve made some good songs over the years. The way it happened is that, after that first session, we were like, We should try to fill up the tape. However many minutes that is, and it will be a record. And we had to plan another weekend because we didn’t all live in New York. We put another weekend on the calendar, then another and another. And eventually, once we’d finished it, we had a little party and invited our friends and gave out cassettes. Then we were like, Let’s do it again! Then we made a second album. Then a third. And we played a couple of shows. And now people have kids and are far-flung, so we’ve slowed down, but we’re currently working on the fourth record. It’s been a real joy. And one of the big things I learned from it… for me it was a real creative unblocking in a sense, like, OK, anyone can do this. I had a strong ingrained sense somehow of, Other people can do this, but not me—you have to really know what you’re doing before you get started or something? So it was a really liberating experience for me.

JTP: That kind of creative approach it’s a little antithetical to writing—or maybe it could resonate with first drafts, with getting something down on the page no matter what. But I think your work—you can feel a sort of improvisatory vibe that the substance of your writing evokes. Not that it’s created in that manner, but what your stories describe often seems to approach that kind of ‘let’s just try this’ creative experience.

ZW: What I like about writing short stories is that it contains both of those worlds [the spur-of-the-moment improvisation and the practiced revision], those aspects. It is really fascinating to me, like, those story ideas that come out of the blue during insomnia—I’m really fascinated by ideas in that way. The moment you’re struck by an idea, when you suddenly have something that wasn’t there just a second ago. It’s just strange. You’re not in control of that. There are so many things that you can’t plan: you just have to kind of wait for it, or be around when it’s there. Or put yourself in a position where it’s going to be there. And the whole process is like that. It’s like that Donald Barthelme thing, that essay he wrote, “Not Knowing,” where he says the writer is one who does not know what he’s doing. That not knowing is crucial to fiction-writing. Not knowing permits what he calls the scanning process; you’re always casting about for something without knowing what it is until you find it and put it in the draft. So the draft kind of grows in that way? There’s the idea that sparks the story. Then there’s a succession of other ideas as you’re drafting. And even revision is not that different in some ways. Because you carry a story with you for a long time and so you’re always dependent on new ideas, even at the line-level.

—> Part II (shorter, much shorter), where Zach Williams talks about the experience of breaking through, will run in about a week.

Zach adds shortly before the publication of this interview: “I did take my son to see Superman (2025), and it was fucking terrible, and my son was too young for it and it frightened him, and I intensely regretted the whole thing.”